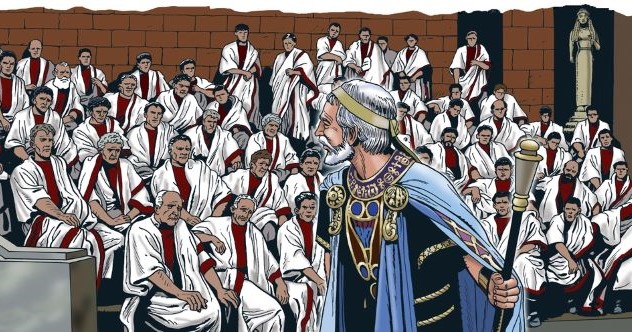

In the Ancient Roman calendar, the Ides was the 15th day of the month that marked the full moon’s arrival. However, after March 44 BC, it forever represented a milepost in Roman politics. On that day, while attending a meeting in the Senate, Julius Caesar was stabbed to death by over 40 knife-wielding senators. The aftermath of the murder, ironically carried out to safeguard the Republic, led to the rise of Roman imperial rule, with Caesar’s grandnephew, Octavian, serving as its first emperor.

Of course, Caesar’s assassination and the events of the Ides of March have been seared into our minds thanks to literature and popular culture. However, this list doubles back to a century before the event to forecast a callous political atmosphere that culminated in Caesar’s body lying on the Senate floor.

This period, labeled the Late Roman Republic, was the political Wild West. In context, Rome’s expansion brought wealth and increased land ownership opportunities. However, these weren’t distributed equally, and the divide between the wealthy and the lower classes grew, creating a tense political and economic buffer zone that was waiting to be exploited. This ether would give rise to factions, populists, and demagogues, creating a vicious environment that makes Caesar’s assassination look like another day at the office.

Related: 10 Unresolved Questions about Ancient Rome

10 Tiberius Gracchus

Murder of Tiberius Gracchus – Ancient Rome – BBC

In the eyes of the Roman aristocracy, Tiberius Gracchus had won the lottery. Born around 163 BC into the prominent Gracchi family, his father was a consul, and his mother was from the legendary Scipio Africanus clan. As such, Tiberius’s political clout was set to success. However, much to the surprise of the Roman elite, Tiberius’s attention was solely focused elsewhere. After becoming tribune in 133 BC—a position that authorized him to propose laws directly to the popular assembly—Tiberius backed numerous legislations favoring the lower classes at the expense of the elite.

In response to the wealth inequality hounding Rome, Tiberius suggested redistributing public lands to the poor. If passed by the Senate, his plans also aimed to restore the class of small independent farmers. Unsurprisingly, the legislation was met with strong opposition from wealthy landowners and the Senate, who deemed it a threat to public order. Yet, despite opposition, Tiberius’s reforms grew increasingly popular with the masses, which led to widespread tensions and hostilities between factions supporting the legislation and their opponents.

Tensions came to a head on June 13, 133 BC, when a group of senators led by Tiberius’s political rival, Scipio Nasica, confronted him as he attended a meeting in the Plebeian Council. In the ensuing struggle, Tiberius was seized by a mob of senators who proceeded to beat him with wooden stools, then stabbed him multiple times and ultimately dumped his body in the Tiber River. In the wake of his assassination, Rome was grappled by a series of conflicts dubbed the Gracchan Wars. The event emphasized how far the aristocracy was willing to go to protect the status quo.[1]

9 Gaius Gracchus

Gaius Gracchus | 132 – 121 | Roman History DOCUMENTARY

Undeterred by the violent death of his older brother Tiberius Gracchus—and to the horror of the Roman wealthy—Gaius picked up where the former had left. And rubbing salt in the wound, Gaius switched up a notch by proposing subsidized grain distribution to the poor and creating special colonies for the landless outside the city. His programs were envisioned to stabilize the political landscape at the time.

Gaius wouldn’t stop there, though; he also went after the Senate’s powers by including reforms that allowed the election of jurors from the equestrian class, an act that, if passed, would reduce the Senate’s control over judicial systems. His reforms were understandably popular with the poor but were deemed dangerously radical by the elites. Plus, seeing his brother was assassinated for much less, they were worryingly bold.

In 121 BC, a supporter of Gaius was accused of murdering a slave of Lucius Opimius, the then consul. This accusation led the Senate to declare Gaius an enemy of the republic and authorized force against him and his supporters. Forces loyal to the Senate eventually cornered him on the Aventine Hill, where—depending on sources—he either asked one of his servants to kill him or his pursuers decapitated him. Nonetheless, his body was desecrated before his head was mounted on a pike in the Forum as a reminder of the fate awaiting the would-be reformists.[2]

8 Gaius Memmius

Gaius Memmius, Praetor 58 BCE

Not much is known about Gaius Memmius’s pre-political life, except that he was born a plebeian in the 140s BC and joined the military, where he cultivated his political career. At some point, Memmius served as praetor, followed by his appointment as the proconsular governor of the Roman Province of Macedonia. Described as “irritably hostile” by his opponents, Memmius had a talent for rousing speeches and employed it to hurl bitter rhetoric toward the aristocracy. Following his election as tribune in 111 BC, Memmius stirred the public against a controversial treaty the Senate had negotiated with King Jugurtha, a Numidian king at war with Rome.

Citing the treaty, Memmius accused several senators and some powerful figures of corruption by colluding with the enemy. Besides anti-corruption, Memmius also championed the already controversial land distribution legislation, except he added a cap on public land ownership per individual. Regardless, Memmius served his entire tribunal tenure with no incident, a rarity considering.

In 100 BC, Memmius ran for consul—a position with almost unlimited executive power—against Gaius Servilius Glaucia, a prominent figure and politician. Still, by all accounts, Memmius had favorable odds. Tensions were predictably high on election day, and fearing a potential loss, Glaucia incited a riot among his supporters. In the ensuing carnage, an angry mob attacked and killed the prospective consul in broad daylight. The public outrage caused by Memmius’s murder was widespread. His murder further led to the entrenchment and growing factionalism in Roman politics.[3]

7 Lucius Apuleius Saturninus

Rome 104 – 101 BC | The Rise of Lucius Appuleius Saturninus

Lucius Saturninus’s early life and activities before his eventual political fame are sparse. Likely born in the early 130s BC, he is believed to have had a stint in the military—a common path for Roman politicians. There, he gained initial popularity. He ultimately gained prominence when elected Tribune of the Plebs in 104 BC and championed popular legislation, including allocating public land to veterans returning from campaigns.

Seemingly outnumbered and at odds with the Senate for most of his tenure, Saturninus aligned himself with Gaius Marius, a controversial general and part-time populist sympathizer. Although it bolstered his political position, earning him re-election, the alliance further heightened his tensions with the Senate. They climaxed in 100 BC after Saturninus proposed a series of controversial legislations that further favored the plebians.

The Senate opposed and accused him of intentionally trying to incite riots using his populist reforms. This led to a political stand-off, which threw the city into unrest, with groups from both sides hunting each other down. At some point, Saturninus was pursued through the streets by a senatorial faction and ironically sought refuge in the senate building. Nevertheless, his men betrayed him to the besieging mob, who tore off the roof, and from there, Saturninus was stoned to death.

Saturninus’s death led to increased efforts by the Senate to stifle the momentum his populist initiatives had created. This led to widespread dissatisfaction, and riots erupted among the lower classes.[4]

6 Gaius Servilius Glaucia

Marian Reforms and their Military Effects DOCUMENTARY

In 100 BC, shortly after orchestrating Memmius’s assassination, Gaius Servilius Glaucia was similarly assassinated after he was caught in the crossfires between the rising political factions. Capitalizing on one of these blocs, known as the populares or populists, who claimed to represent the interest of the commoners, Glaucia had aligned himself with Lucius Saturninus. Together, they fought to oppose the Senate’s authority.

Besides the land issues, they most notably proposed expanding the rights of the equestrian class, comprised of wealthy non-aristocrats but otherwise very influential figures in Roman society. It was a political maneuver to expand their support base against the Senate. Not to mention, Glaucia’s unscrupulous use of violence and intimidation to solidify his position further alienated many and deepened that rift. In the ongoing deadlock, Rome was gripped by violent riots perpetrated by their supporters.

In response, the Senate issued a decree allowing extreme measures to be taken against those deemed a threat to the Republic. Included in the list were Glaucia and members of his clique. Glaucia, meanwhile, attempted escape by seeking refuge inside the temple of Jupiter. But he was besieged and was captured by the Senate’s forces, who then beat him to death before throwing his body down the temple steps.

The brutal nature of Gaius’s assassination saw former supporters and political allies reassert their positions, as had become the norm. Besides being a huge blow to the Gracchan faction, his death would contribute to the cycle of violence that characterized the period.[5]

5 Marcus Livius Drusus

Rome 95 – 91 BC | Marcus Livius Drusus Rising

Marcus Livius Drusus was an unconventional politician of his day. While his contemporaries were solely focused—and tearing each other apart—on the constant factional rivalries inside Rome, Drusus was looking outside, particularly at Rome’s Italian allies, advocating for their rights and further recognition. During his term as tribune, Drusus famously introduced a series of legislations that included expanding citizenship to the allies. These initial efforts were fragments of a larger push to address their pre-existing and ignored grievances, which had seen them further excluded from the numerous benefits enjoyed by their Italian peers.

Unsurprisingly, in a political climate where granting grain relief to the city’s poor was deemed fanatical, Drusus’ reforms were met with fierce opposition and were promptly outlawed by the Senate. Yet, despite his precarious position, the undeterred Drusus advocated for his proposals. Meanwhile, many would never forgive his Roman citizenship to the Allies scheme.

In 91 BC, while on his way home one evening, Drusus was ambushed by a group of assassins. After a short chase, they cornered him —as he sought refuge in a friend’s home—stabbed him multiple times and left his body in the streets. Since Rome’s allies considered it a martyrdom, Drusus’ assassination ignited tensions that resulted in the outbreak of the Social War (91-88 BC), which ended after Rome accepted to grant them citizenship.[6]

4 Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo

Optimates and Populares in Late Republican Rome

Around 131 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo, alias Vopiscus, was born into the influential Julian clan, then at its peak in Roman politics. Though separated by several generations and from different branches of the family tree, Strabo and the future-famous Julius Caesar shared a common ancestor. The future dictator is said to have admired Strabo’s political dialogues, which inspired his speeches. Tragically, in hindsight, the young dictator should have perhaps studied Strabo’s fall.

Politically, Strabo served as an aedile, a position that, among other things, put him in charge of public works and games in the city. Around this time, Strabo got involved with the ongoing conflict between two factions: the populares and the optimates. In a violent deadlock on how power should be distributed, the populares proposed the wishes of the common people should bypass the traditional senatorial authority. On the other hand, the optimates defended the status quo.

By 87 BC, and already an outspoken supporter of the populares, Strabo would twist the proverbial knife when he made a controversial bid for the consulship without standing for the praetorship first, as was the norm. Using this as a pretext to protect the Republic, a mob of armed senators, under the leadership of Gaius Marius, confronted Strabo, alongside his brother Lucius, in the streets of Rome. The two brothers were hacked to death in the ensuing clash, and their heads were later put on public display. The brazen murder of the Julii brothers highlighted how toxic Roman politics had become.[7]

3 Publius Clodius Pulcher

Cicero and Clodius: Best of Enemies

The Claudii was a distinguished clan in Rome, and it featured several figures and would-be Roman emperors. In 93 BC, a new member was born: Publius Clodius Pulcher. By leveraging his family name, Clodius’s career quickly soared. His political appointment coincided with the raging tensions between the populares and optimates. Sizing his prospects, he cast his lot with the former. Afterward, armed with plebeian support and an army of thugs beside him, he bullied his way to the position of tribune. Consequently, to his opponents, Clodius had become the embodiment of a populist fanatic.

In 62 BC, Clodius was entangled in a scandal after it was revealed that he had snuck into The Bona Dea—a sacred rite only reserved for women—disguised as a woman. Among those in attendance was Terentia, Cicero’s wife. Understandably, the incident—plus Cicero was a staunch optimate—didn’t sit well with the famous orator, and it ignited a public feud. Yet Clodius kept stumbling from one scandal to another, alienating close allies.

Still, Clodius got embroiled in another feud with a prominent optimate, Annius Milo. However, unlike Cicero, Milo took his political grudge from the Senate floor to the streets. On January 18, 52 BC, while returning to Rome from a trip, Clodius crossed paths with Milo on the Via Apia, on the fringes of Rome. The two men and their armed entourage clashed, and Clodius was bludgeoned to death. His body was then dragged to the streets of Rome to be desecrated and displayed.

Clodius’s murder spelled doom for the Republic; it left a power vacuum that led to significant shifts in Roman power dynamics that exacerbated the stage for the eventual transition to the Roman Empire.[8]

2 Lucius Cornelius Cinna

Lucius Cornelius Cinna, Praetor 44 BCE

Besides being Julius Caesar’s father-in-law, Lucius Cinna was also an alumnus of the Social War (91-88 BC) and served as legate. This stint saw him rise through the political ranks, eventually becoming a key figure in the Marian faction—which subscribed to reforms proposed by Gaius Marius. In 87 BC, Cinna was elected consul, a position he would hold on to, serving four consecutive terms. His election coincided with significant conflicts caused by Sulla, a rogue Roman military commander who had marched on Rome, causing turmoil.

In response, Cinna waged a civil war against Sulla’s supporters. Cinna also locked horns with the Senate numerous times, thanks to an alliance with the previously exiled Gaius Marius. Together, they went on a political cleansing, stopping at nothing to crush their enemies. This led to even more tensions, culminating with Cinna’s expulsion from Rome. However, Cinna returned with an army behind him and resumed terror on his political rivals.

In 84 BC, Cinna was preparing for a military campaign against Sulla when his troops—depending on sources, either dissatisfied with his overly tyrannical rule or bribed by his enemies— mutinied. Following an assembly to address the unrest within his ranks, Cinna was mobbed and killed. Exact details vary, but it’s generally believed that he was stabbed multiple times.

Cinna was one of the last prominent members of the populares. His death led rival factions, particularly the optimates, to bolster their strength in the Senate.[9]

1 The Man Who Gives Dictators a Bad Name

Lucius Cornelius Sulla | Rome’s brutal dictator

Lucius Cornelius Sulla wasn’t assassinated; he appears on this list solely because of his victims. Despite being born a patrician in 138 BC, Sulla was reportedly not that wealthy growing up. He caught a break in the military, where his exploits in the Social War saw him soar through the ranks. Finally, in 88 BC, he was appointed commander of the Roman armies but faced opposition from Gaius Marius and his supporters.

In response, Sulla performed a shocking “historical first” when he marched on Rome and captured the city (setting a precedent for Julius Caesar, who would famously cross the Rubicon decades later). However, Marius had died by the time Sulla settled in as dictator. Not to be held back, Sulla turned his attention to Marius’s remaining supporters to nurse his itching grudge. That came in the form of the dreaded Proscription Lists.

Also known as Sulla’s lists, they included around 80, later expanded to 200 and then 800 individuals. Names unlucky enough to end up on the list meant confiscation of property and execution (though sometimes just the former) without trial. Updated and published regularly in public spaces, they targeted prominent figures, senators, and the wealthy.

Once the list was posted, Sulla’s murder squads would then roam the streets to hunt down the proscribed. Seeing historians estimate between 1,000 and 9,000 victims, Sulla’s purge lists deserve a separate list. Still, figures like Marcus Lepidus, Quintus Sertorius, and Publius Rufus are just a few examples of politicians whose fates were sealed by the lists. Even Julius Caesar and Gnaeus Pompey were at some point targeted but managed to survive.

Sulla’s proscriptions were notoriously arbitrary; names could be added based on multiple reasons. It didn’t matter which faction an individual belonged to; even Sulla’s sycophants would regularly appear on the lists. Attempts to assassinate him further exacerbated the carnage, resulting in lists becoming longer and more belligerent. Sulla’s reign of terror was unique even for the serial Roman survivalists. Seemingly satisfied with his murderous streak, Sulla retired from office in 79 BC—a rare and odd move, considering—to seemingly enjoy his ill-gotten wealth. He later died of old age at his countryside villa.

His reign of terror is deservedly a grim chapter in the Late Republic’s story, for it marked the moment Rome tasted bitter autocratic rule. Perhaps it was the memory of that chapter, ingrained in the minds of those 40 knife-wielding senators, that led them to put an end to Julius Caesar after he was declared dictator for life![10]

fact checked by

Darci Heikkinen