President Donald Trump arrived at Ben Gurion Airport on Monday morning, October 13th, just as Hamas was releasing the last surviving Israeli hostages after two years of cruel captivity and Israel had halted its devastating bombardment of Gaza. Since October 7, 2023, two thousand Israelis and sixty-seven thousand Palestinians had been killed. The Strip had been reduced to a landscape of destitution and ruin. A ceasefire that could, and should, have come long ago was finally, fitfully, taking hold.

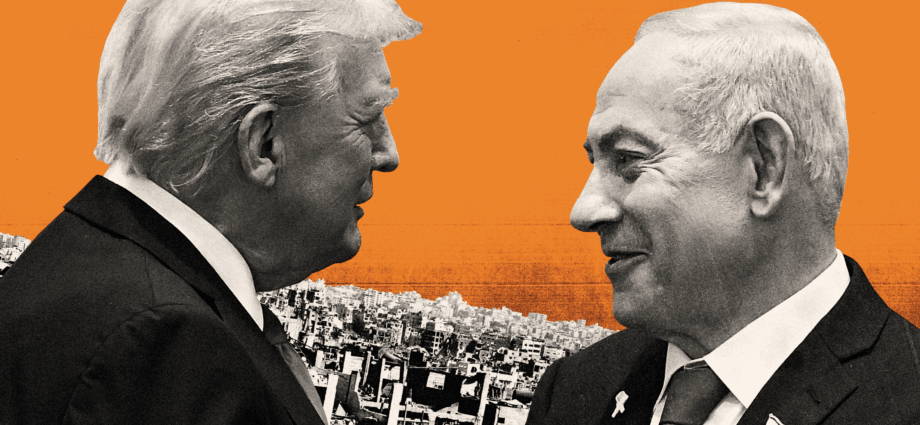

In Jerusalem, Trump was greeted on billboards and in the Knesset as a modern Cyrus the Great—the Persian ruler who, in 538 B.C., allowed the Jews to return to the Holy Land from their Babylonian exile and rebuild the Temple. During Trump’s speech to the Knesset, two left-wing lawmakers, Ofer Cassif, a Jewish Israeli, and Ayman Odeh, a Palestinian Israeli, raised small placards reading “Recognize Palestine.” Guards swiftly hauled them from the chamber. The President praised the speed with which this modest protest was suppressed. “That was very efficient,” he said brightly. In his self-admiring rambling, Trump took time out to thank his lead negotiator, Steve Witkoff (a “Kissinger who doesn’t leak”), and one of his wealthiest patrons, Miriam Adelson (“She’s got sixty billion in the bank!”), then turned to trash Joe Biden—the “worst President in the history of our country by far, and Barack Obama was not far behind.”

It is impossible not to feel immense relief that this long, terrible war may at last be ending; it is also hard to ignore that the President’s decision to apply his sense of leverage and cunning to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu owed little to consistent strategy, empathy, or conviction. Indeed, his reckless musings earlier this year about making Gaza a “Riviera of the Middle East” stoked the Israeli right’s fantasies of resettling the Strip and annexing the West Bank. They also deepened much of the world’s anger. The pivotal moment came on September 9th, when Netanyahu ordered an air strike on a residential building in Doha, hoping to kill four Hamas leaders who were then engaged in ceasefire negotiations. The strike missed its targets but clearly rattled Trump.

Like so many Presidents before him, he had indulged Netanyahu’s propensity to take American military and political support for granted. But the strike on Doha touched something more sensitive than principle: the bottom line. The Trump family’s business ventures are increasingly entwined with Qatari and Gulf capital. Trump compelled Netanyahu to deliver a scripted apology to the Qataris— a humbling that restored their confidence and amour propre, reassured Turkey and Egypt, and led these regimes to press Hamas into accepting the pending ceasefire agreement. The most consequential Israeli air strike of the war, in the end, was one that failed.

The President now hails “the historic dawn of a new Middle East.” When, during the hopeful years of the Oslo Accords, Shimon Peres used that phrase, he was mocked for his naïveté. Trump’s version owes less to diplomacy than to real-estate patter, the it’s-so-if-you-believe-it’s-so spirit he called on when insisting that Trump Tower had sixty-eight floors, though it actually had fifty-eight. As much as the President prizes “deal guys” over starchy diplomats, however, attaining peace in the Middle East is not so simple as unloading a defunct casino. The Administration cannot just declare an end to what the President calls “three thousand years” of conflict and move on to its domestic project of undermining the rule of law. History resists the shortcut.

The idyll of a “new Middle East” in Netanyahu’s triumphalist view is one in which, owing to his Churchillian leadership, the threats from Hamas, Hezbollah, Syria, Yemen, and Iran are all diminished or defeated. Behold the dawn. As for Netanyahu’s failure to safeguard the country on October 7th? All is forgotten. This willfully blinkered vision, or, more precisely, reëlection platform, ignores the cost in global opinion along with the moral and political fractures within Israel itself. It also overlooks the rage bred into the bones of young Palestinians, who have lost family members and friends but not their insistence on dignity and a home. Real progress in the region, real justice and stability, will require healing, constancy, imagination, and endurance—day after day, year after year, long past any one Administration.

By Wednesday, when Hamas had transferred only a fraction of the remains of dead Israeli hostages, Israeli officials threatened to cut humanitarian aid to Gaza. Meanwhile, Hamas, which Israel is aiming to disarm, was executing rival Palestinians in the streets of Gaza City. The questions now are many: Who will pay for the rebuilding of Gaza? Who will govern it? Will Israeli troops remain in the Strip? And, above all, what becomes of the “credible pathway to Palestinian self-determination and statehood” that the ceasefire agreement hazily invokes? Talk of a solution—of two states, of a confederation, of nearly any prospect for a secure and free mode of coexistence—has long been dismissed as either an ingenuous assertion of faith or a cynical pantomime, an empty gesture toward a future no one expects to see.

Such resignation is both understandable and impermissible. Watching Trump and Netanyahu at the Knesset, one sought a more inspiring spectacle, such as one that took place in the same chamber on November 20, 1977. After thirty years of hostilities, Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat flew to Jerusalem, extended his hand to Menachem Begin, and spoke to the Israeli lawmakers:

I have come to you so that together we should build a durable peace based on justice, to avoid the shedding of one single drop of blood by both sides. It is for this reason that I have proclaimed my readiness to go to the farthest corner of the earth. In all sincerity, I tell you we welcome you among us with full security and safety.

Neither Sadat nor Begin were innocents or doves. Sadat so despised the British colonialists that he wrote a letter to Hitler, as if the dictator were still alive, that began, “I admire you from the bottom of my heart.” Begin, for his part, was a militant in the Zionist underground, denounced by David Ben-Gurion as a “racist” and a “distinctly Hitleristic type.” And yet, with the sustained mediation of an American President, Jimmy Carter, the two men found a way to forge a peace that endures still.

Sadat’s gesture belongs to another age, when courage meant accepting risk rather than projecting swagger. What unfolded in Jerusalem last week seemed less like a “new Middle East” than a reprise of its oldest patterns: the vanity of leaders who mistake declarations of triumph for true resolution, and the endurance of those left to shoulder the consequences. The work of justice, as ever, falls not to those who proclaim history’s dawn and move on but to those who must push through its long and gruelling day. ♦