Books & the Arts

/

June 23, 2025

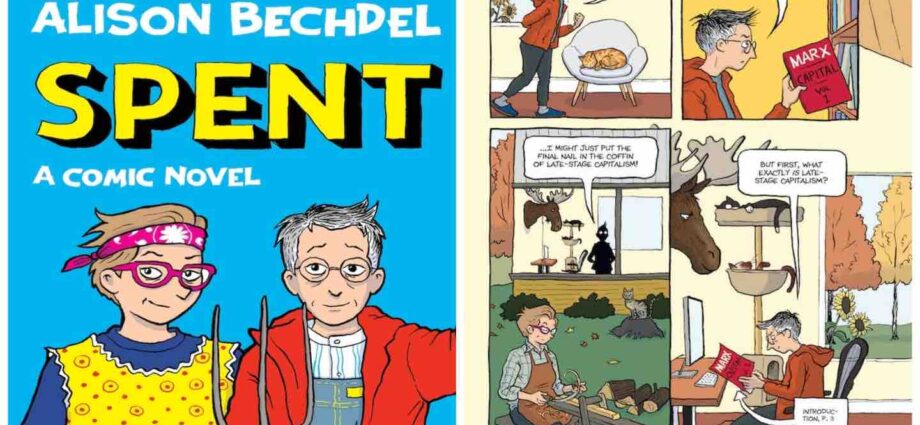

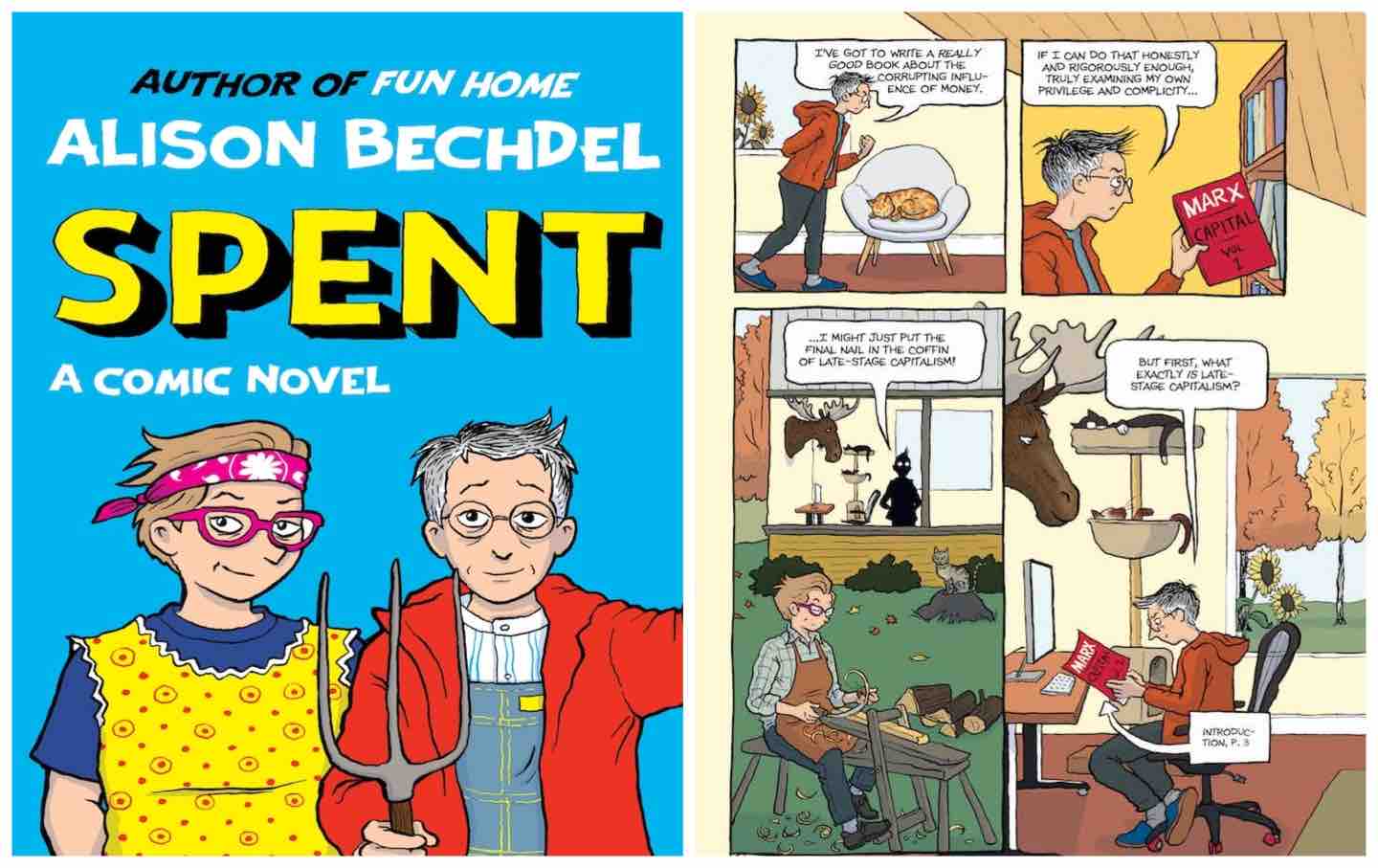

In Spent, the graphic novelist confronts aging, politics, sex, and what it means to succeed under capitalism.

Excerpted from the book Spent, provided courtesy of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2025 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission.

In the early aughts, Alison Bechdel was a struggling cartoonist. She’d been writing and drawing her comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For—about a group of mostly lesbian friends and lovers—since 1983, building a cult following in the process. But in the 2000s, the business model that had sustained her for decades started to unravel, as the advent of the Internet reshaped the entire media landscape. Bechdel had long syndicated the series in alternative newspapers (queer ones and the humor publication Funny Times), but they began to shut down; then the lesbian feminist publisher of her collections of the strip went bankrupt in 2002. When her agent tried shopping around a Dykes collection, editors at other houses mostly passed, saying, “People don’t need this work the way they once did.”

Books in review

In 2006, while worrying about the sustainability of her future as a cartoonist, Bechdel published Fun Home. The book, which she’d been working on for seven years, was a graphic memoir about her relationship with her father, who died—by suicide, Bechdel speculates—shortly after she came out to her parents. Fun Home was unlike anything she’d published before. Whereas Dykes was topical, conversational, witty, and episodic, Fun Home was introspective, analytical, archival, and long-form. It represented a gamble that her readers would follow her into new territory and a medium—the graphic novel—that was only just starting to gain traction in American literary culture.

The gamble paid off, and probably more than anyone, including Bechdel, could have anticipated. Fun Home received rave reviews, including one in The New York Times Book Review that called it “a pioneering work, pushing two genres (comics and memoir) in multiple new directions”; it spent two weeks on the Times’ bestseller list and was nominated for and won multiple awards. Years later, the book was adapted into a Tony Award–winning musical. “It saved me,” Bechdel told an interviewer in 2021, reflecting on the success of Fun Home. “But then I was in this whole different relation to the world.”

That different relation to the world is, in part, the subject of Spent: A Comic Novel. Bechdel’s latest graphic novel tells the story of a fictional Alison Bechdel who lives in Vermont with her partner, Holly. (The real Bechdel also lives in Vermont with her partner, Holly Rae Taylor.) The two run a pygmy-goat sanctuary, living largely off of the money that the fictional Alison has made from the TV adaptation of her highly successful graphic memoir about her dad. (In Spent, her father is a taxidermist, and her book is called Death and Taxidermy; in real life, Bechdel’s dad worked as an English teacher and an undertaker—hence Fun Home, her family’s term for the funeral parlor.)

Spent follows the adventures of Alison, Holly, and their group of friends—some of whom are characters from Dykes to Watch Out For, returning after a long hiatus. (The series is retooled here as Lesbian PETA Members to Watch Out For, one of the many funny naming flourishes that Bechdel sprinkles throughout the book.) And just as in Dykes, we follow them through the travails of daily life—work, politics, relationships, sex, and aging. In many ways, Spent finds Bechdel harking back to her roots by taking up fiction and a contemporary communal narrative once more.

Yet it also marks a departure of sorts—or, perhaps more accurately, a next step. The original Dykes strips, which Bechdel began when she was in her 20s, were often funny, but as a project, they were earnest: an attempt to represent her life and the lesbian world she inhabited in popular culture. That’s part of what made them groundbreaking in the 1980s and ’90s. In turn, Fun Home and Bechdel’s follow-up book, Are You My Mother?—published in 2012, about her relationship with her mom—were deeply inward-facing, rigorous attempts to know and understand herself and where she came from. (Are You My Mother? includes countless scenes of Bechdel in therapy.)

For her third graphic memoir, The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Bechdel turned her attention to her lifelong love of exercise—which, as she writes in that book, is a “quest to get out of my head and transcend my ego.” It’s notable that Bechdel had just turned 60 when Superhuman Strength came out in 2021; the book is partly about the inevitability of death. Now, with Spent, which is her first stand-alone fiction project, I get the sense that Bechdel’s search for enlightenment has been semi-successful: Something freed her up to make a book so quickly—and in full, bright color, unheard of in her oeuvre!. At the same time, Bechdel knows that complete transcendence of the self is impossible, so she’s chosen the next best thing: satirizing it.

Spent has an abundance of characters and storylines. There’s Alison, who feels enormous pressure to pull off her next big project but is so distractible and neurotic that she can’t get anything done. (At times, Alison seems like a more mature version of Mo, Dykes’ politically obsessed killjoy, who is widely recognized as a stand-in for the author.) Her working idea is $um: An Accounting, a graphic memoir that will also be “a lens into the over-consumption, endless growth and media consolidation of late-stage capitalism!” Those qualities are embodied by the TV adaptation of Death and Taxidermy, which Alison and her friends gather to watch. The series has strayed so far from the book it’s based on that it features Alison murdering her brother and somehow eating her mother… plus, there are dragons. When Alison objects, the showrunner, Cedilla Ümlaut, snaps, “I don’t think you grasp the forces at work here. I’m making something that has to excite audiences! Win awards! Please bean counters!” (Cedilla also later reminds Alison, coolly, that she’s signed away all her rights.)

What’s more, Alison’s sister, Sheila—a famous seed artist and member of a right-wing group called Liberty Mothers—decides that she wants to tell her own version of their childhood story and sends Alison her unwieldy, handwritten manuscript. Holly, Alison’s partner, makes a wood-chopping video that goes viral and then attempts to strike gold again.

At the same time, Alison’s friends Ginger, Lois, Stuart, and Sparrow live in a communal house—which they did in Dykes, too, when they were younger. Stuart and Sparrow’s longtime relationship is stagnant and acrimonious—until they reconnect with an old flame, Naomi, at the local food co-op and undertake an experiment in polyamory. While that’s unfolding, Stuart and Sparrow’s child, J.R., drops out of college and returns home with a friend in tow: They’ve decided to become full-time activists. The kids host a podcast called Polycrisis, which “look[s] at climate change and the economy through a poly, anti-capitalist, vegan lens.” It’s so successful that they land Bill McKibben as a guest.

The flow of all this can occasionally become unwieldy, and at times it’s hard to locate the book’s center of gravity. But the reader never gets truly lost: Bechdel weaves the plot strands together in an entirely navigable way—a skill she learned from decades of writing and drawing Dykes. And if the narrative is laden with details (and Easter eggs), that’s at least partly by design: Spent is very much about the overwhelmingness of today’s world. Alison may be hopeless at concentrating, but it’s not completely her fault—distractions are everywhere. In one moment, as she goes outside to take in a beautiful spring morning, her smart watch beeps with a mindfulness alert: “Reduce stress by taking time to reflect.”

Spent coheres partly through its structure: Each chapter is named after one in Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, which Alison starts reading when she realizes that if her book is going to “put the final nail in the coffin of late-stage capitalism,” then she needs to know what exactly late-stage capitalism is. Bechdel’s previous books are filled with discussions of writers as wide-ranging as James Joyce, the psychologist Donald Winnicott, and the transcendentalist Margaret Fuller. Engaging with Marx, then, is purposeful: Bechdel tends to build her narratives via a certain critical and interpretive mode—of both the literary and psychological varieties.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Yet in Spent, the Marx references are also a joke, since the cleverly chosen phrases loosely reflect what unfolds in each chapter. For instance, the section where Alison flies to Los Angeles to pitch a reality-TV version of $um is titled:

The Circumstances which, Independently of the Proportional Division of Surplus-Value into Capital and Revenue, Determine the Extent of Accumulation, namely, the Degree of Exploitation of Labour-Power, the Productivity of Labour, and the Growing Difference in Amount Between Capital Employed and Capital Consumed, and the Magnitude of the Capital Advanced.

It’s ridiculous, but also a wink to the reader: You don’t need to have read Marx to intimate the connection between pitching a TV show and “the Magnitude of the Capital Advanced.”

What makes Spent unusual for Bechdel is the fact that the intertextual citations are otherwise not part of how the story is told. (In fact, in one of the book’s many meta moments, we see Alison ask her editor on a Zoom call, “Did you notice I took almost all the Kapital excerpts out?”) Instead of filtering the plot through the observations and lives of others, as has often been her way, Bechdel is speaking directly to her readers here—quite literally, through a third-person, omniscient narrator. The narration is by turns forthright, pensive, and archly knowing—a panel depicting Stuart, Sparrow, and Naomi in the throes of sex is accompanied by a caption box that reads: “Indeed, they give ‘sandwich generation’ a whole new meaning.”

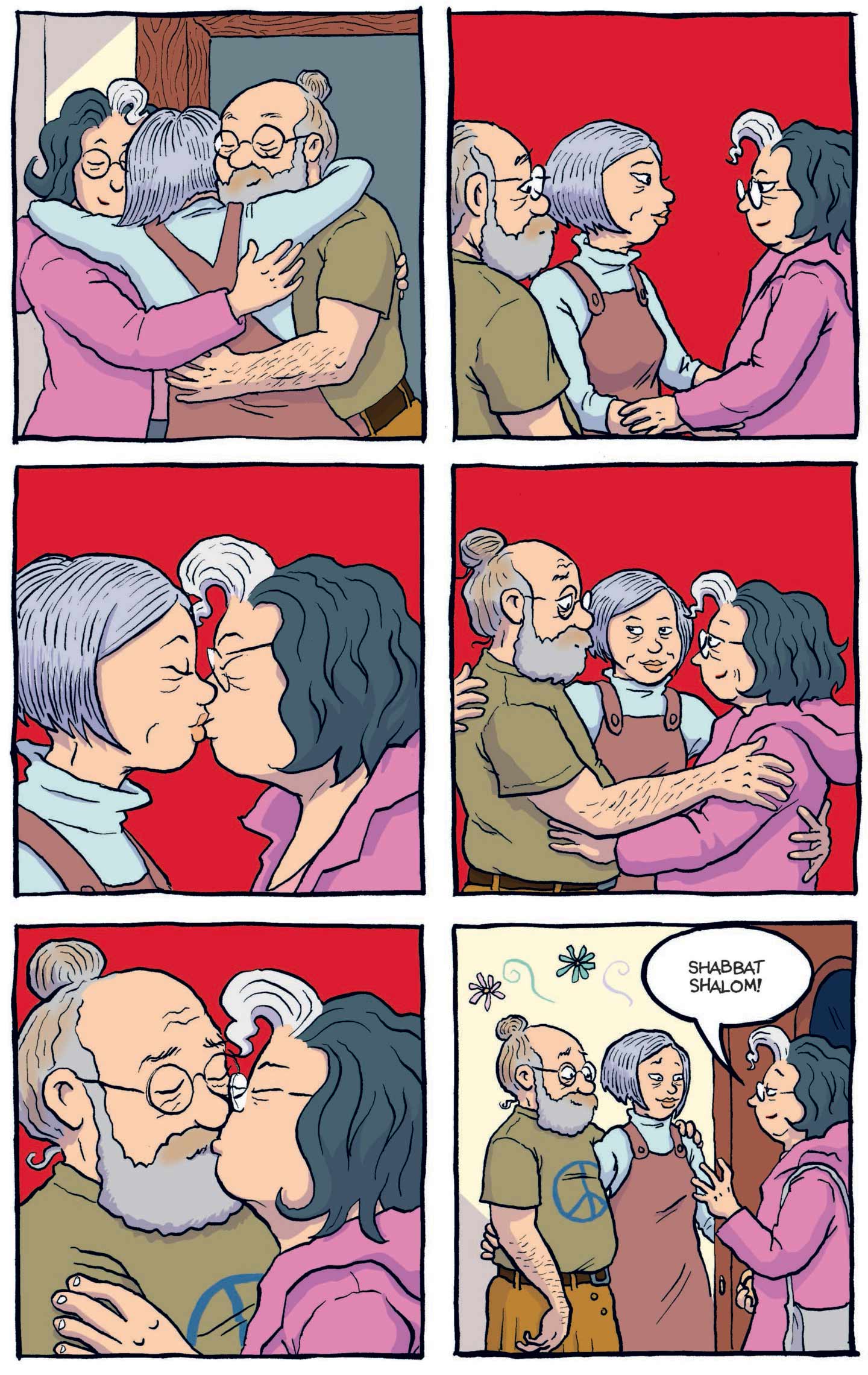

Despite the cheeky line, that drawing of the threesome is rapturous. It points to one of the joys of Spent: its depiction and embrace of the intimate lives of the over-60 set. Bechdel’s renderings of the polycule are particularly tender, like the scene where Naomi kisses Stuart and Sparrow for the first time. The six-panel page is nearly wordless—a rarity in a Bechdel book—as the trio savor each other against a bright red background.

In many ways, Spent is as much about pleasure as it is about chaos, whether that’s the pleasures of the flesh or the simpler delights of curling up with a cat or sitting by a fire under the stars. The feeling also comes through in the book’s full-color palette, which is rich with reds, purples, blues, and greens. Bechdel has been very slow to embrace color: Fun Home was washed solely with a melancholy blue, Are You My Mother? with an archival red. Superhuman Strength marked the first time that she brought more hues into her work, via a labor-intensive collaboration with Holly Rae Taylor. Yet even then, they remained light and largely pastel—more evocative accent than driving force. In Spent, the colors are stronger and more prominent; Taylor’s work feels like it’s become an engine of the story, just as Holly the character is, too. It contributes to the sense that Bechdel’s scope of inquiry has expanded, and that the book is alive and alert to the present day.

For most of Spent, the plot is so absorbing and the tone so jocular that you’d be forgiven for missing the larger point. (One of my favorite visual gags is the large moose head on the wall of Alison’s office—it never moves, but its expressive eyes shift, as if constantly judging her.) And then, in the final spread, the narrator comes right out and states it: Despite her anxiety about the future, Alison “knows…she will get by with a little help from her annoying, tenderhearted, and utterly luminous friends.”

The line is a bit pat, but it speaks to one of the strengths of both Dykes and Spent: Bechdel’s ability to use her friends as foils for her own follies. If we’re lucky, we all get to do this, but it’s a hard process to depict on the page, at least in prose. Comics, by contrast, are a ready vehicle for dramatizing conversations. For instance, right before the final spread in Spent, Alison has an “aha” moment. As she explains it, “I was paralyzed because I thought I somehow had to fix everything myself!” To which Ginger responds, in her trademark deadpan, “That’s the most narcissistic thing I ever heard.” Touché.

In addition to being a zinger, though, Ginger’s comment hits on something important: Spent is about more than friendships per se. It’s an assertion of the idea that politics is about lived experience—that hashing it out with others, whether they’re your friends, family, or fans, is not only inescapable, but actually the only way to survive in a world that at times feels beyond saving. Spent suggests that we just might be able to help save each other, if we learn to accept the inherent messiness and contradictoriness of life. It’s a simple but vital message, and one that bears repeating.

What’s notable, too, is that Bechdel is clearly putting into practice what she’s preaching. Spent sees her trying to move out from the long shadow of memoir—modeling the idea of pushing forward and not getting stuck in the past. The book is still about her, but not wholly; it’s also a story told, lovingly, at her own expense. Decades of introspection have ultimately led her to look out.

Thankfully, she hasn’t fully jettisoned her trademark earnestness or passion—every Bechdel project is an attempt to answer a Big Question—but she has found a way to treat those qualities with a lighter touch. Spent is an attempt to merge the early lessons of writing and drawing Dykes with those learned from the more mainstream books that followed. It’s a gambit for how to be in relation to a daunting world. In the end, Bechdel insists that there’s value in trying to shape something meaningful from the chaos—just as long as it’s not reality TV.

Be part of 160 years of confronting power

Every day, The Nation exposes the administration’s unchecked and reckless abuses of power through clear-eyed, uncompromising independent journalism—the kind of journalism that holds the powerful to account and helps build alternatives to the world we live in now.

We have just the right people to confront this moment. Speaking on Democracy Now!, Nation DC Bureau chief Chris Lehmann translated the complex terms of the budget bill into the plain truth, describing it as “the single largest upward redistribution of wealth effectuated by any piece of legislation in our history.” In the pages of the June print issue and on The Nation Podcast, Jacob Silverman dove deep into how crypto has captured American campaign finance, revealing that it was the top donor in the 2024 elections as an industry and won nearly every race it supported.

This is all in addition to The Nation’s exceptional coverage of matters of war and peace, the courts, reproductive justice, climate, immigration, healthcare, and much more.

Our 160-year history of sounding the alarm on presidential overreach and the persecution of dissent has prepared us for this moment. 2025 marks a new chapter in this history, and we need you to be part of it.

We’re aiming to raise $20,000 during our June Fundraising Campaign to fund our change-making reporting and analysis. Stand for bold, independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Publisher, The Nation

Jillian Steinhauer

is a critic and reporter who covers the politics of art and comics. She won a 2019 Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.