A conversation with the medical sociologist about her new book, Get It Out, and the perils of considering abortion, hysterectomy, and gender-affirming care as separate issues.

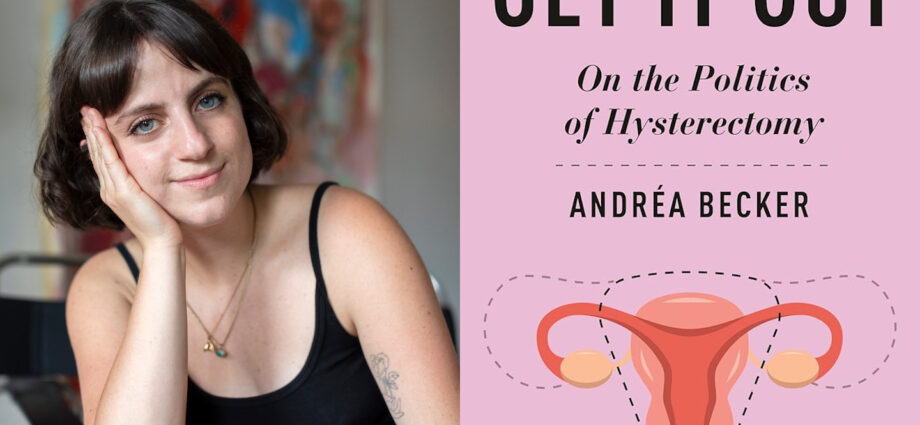

Andréa Becker, PhD, is a medical sociologist specializing in contested medical practices—“elements of medical care imbued with polarizing cultural meanings.” Her new book, Get It Out: On the Politics of Hysterectomy (New York University Press), explores the ways in which both actual and perceived access to hysterectomy are stratified by race, age, and gender identity. She powerfully connects the dots between eugenic policies and their continued impact on reproductive health care and the ability of patients to have a sense of bodily autonomy and reproductive agency. I spoke with Becker, assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at Hunter College–CUNY, about the timely implications of her findings; the perils of considering abortion, hysterectomy, and gender-affirming care as separate issues; and how much has changed in American politics since she completed the writing of her book.

Sara Franklin: In the opening paragraph of your book, you write, “Having a uterus is a relentless job…. Simply having a uterus is the shift that never ends.” You’re drawing a comparison to the idea of the “second shift” that women do with domestic labor—childcare and household duties—in general. There’s also this interesting tension related to the way a person with a uterus is always seen as “potentially” childbearing and child rearing. Tell me about the choice to frame the issue through that lens.

Andréa Becker: I wanted to start the book by drawing attention to the labor that these organs produce or necessitate because of the way that healthcare has reduced them to reproductive. One of the things with endometriosis, for example, is it’s really difficult to get a diagnosis. But it’s far easier to get a diagnosis if you’re trying to get pregnant, because suddenly your doctors care about the functions of these organs, so the odds of getting diagnosed with these diseases goes up if you’re trying to use them for a pregnancy. But if you’re just trying to live a pain-free, happy life, they’re minimized. We all live through this tension all the time. I want people to understand the labor that goes into having these organs, not only with menstruation, but any sort of chronic issue that we have for preventing pregnancy, and that these organs produce social inequalities in these invisible ways. It’s ironic, since I also focus on trans and nonbinary people, to begin it this way. But trans and nonbinary people are also navigating these highly gendered discourses in their health care. Especially if they’re seen as women.

SF: You write about the “moral panics that emerge and proliferate around any health care that disrupts female reproduction,” and ask, “If people can readily remove the very organ that society has used to denote their otherness, how will the gender order be maintained?” That word—order—really struck with me, especially considering the rise of authoritarianism and the use of executive orders to alter norms and policies. How are you thinking about this new world order since the publication of your book?

AB: I began this work before Roe v. Wade was overturned—a lot has happened since. I think we could be slightly more precise and talk about the “ordering” logic of white supremacy and patriarchy. At the root of both attacks on trans health and on reproductive health are eugenics, so I’m trying to bring attention to eugenics logic.

When we talk about eugenics, we tend to talk about, for example, the history of forced sterilization in the United States, of wanting to prevent the births of Black and brown people, of poor people. But we talk less about what’s called positive eugenics, of wanting to increase births. So things like reducing access to fertility, limiting technologies like abortion or birth control—those are intended to increase white births. At the core of this chipping away at bodily autonomy is the desire to increase the fertility rates of some kinds of people, and then reduce the freedoms and fertility of other people. We see both of these things happening simultaneously.

SF: This is one of the most important things in your book—this reminder that regardless of the identity of the person with a uterus in their body, or who had a uterus in their body when they were born, eugenics is hovering in the air all around them. It is alive and well.

AB: People think of eugenics as a historical practice, like when we had formal eugenics boards where people on these committees would decide who should or should not be forcibly sterilized. The Supreme Court actually upheld the right for states to forcibly sterilize disabled people in Buck v. Bell, and it’s never been overturned.

We no longer have formal eugenics boards, but we see trickles of this eugenics logic continuing in healthcare and in the carceral system. It’s eugenics logic at play when migrant women in detention centers aren’t seen as worthy of reproduction, and so forced hysterectomies were deemed acceptable. And then, when we see this growing pro-natalist movement, this growing movement among highly educated white billionaires to increase the birth rates of other white billionaires—abortion bans are fueled by eugenics—we’re continuing to see this desire to repopulate the earth with the “right” kinds of people and to reduce the birth rates of other types of people.

SF: It’s also interesting that, in a very short space of time, the term “fascism” has become more commonly used and understood. Do you imagine that “eugenics” will assert itself alongside “fascism” as we move further into this moment?

AB: Definitely. Often when people think of medicine and healthcare, they think of objective practices based on science. But in a lot of ways, doctors are practicing healthcare within ideologies. So when a cultural landscape normalizes something, it weaves into health care. When we normalize this idea that people don’t have the right to bodily autonomy, then we see it trickling into individual healthcare decisions. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that abortion bans and gender-affirming healthcare bans are proliferating alongside this growing “trad wife” movement—this idea of wanting to return to “traditional” family values. You know, Hitler also wanted to bring back rigid gender roles and rigid ideas around gendered bodies. It’s really key here.

That’s why I focus on hysterectomy. Because when you focus on these individual stories around wanting to remove or not remove a uterus, you start to map onto this larger framework of controlling people’s bodies, of wanting to redraw the boundaries around femininity, womanhood, motherhood. They exist alongside each other.

People who study trans health and those who study reproductive health tend to be separate, but they really inform each other. It’s key to look at them together. It’s the same discourses being used to limit access to both types of care.

SF: The upholding of the Tennessee ban on gender-affirming care for minors is so exactly following the playbook that led to the overturning of Roe. Can you walk us through, in lay terms, this concept that reproduction is stratified along the categories of sex, race, and gender identity?

AB: Stratified reproduction refers to the idea that who we are, where we were born, what we look like determines the degree of freedom we have over our reproduction. So what race you are, what income you have, will determine if a doctor will push an IUD on you or not, whether a doctor will try to preserve your fertility at all costs, or whether they’ll recommend a hysterectomy. In many ways, who you are determines your freedom to choose.

When we think of freedom to choose, we focus on abortion, but it’s so much broader than that. The freedom to have control over your body, the freedom to live a pain-free life, the freedom to not be bleeding the whole month. We don’t even have research on how to cure a lot of these illnesses. We don’t really have up-to-date diagnostic tools.

One of the takeaways that I want my readers to come away with is that gynecology, and the healthcare system more broadly, are designed for cis women having babies. When we reduce bodies with uteruses to being reproductive, it’s impossible to fully treat the entire person. We see this idea over and over again. The NIH budget at the time of writing this book, only 10 percent went into studying women’s health issues and these organs. Even telling women to take vitamin B and folate, that’s rooted in this idea that they’ll one day be pregnant so to get their bodies ready for pregnancy. It’s everywhere.

Stratified reproduction tries to get at this reality that your freedom to choose is limited by these broader cultural, medical, and policy influences.

SF: Right. And then that gets us to this idea that what is seen as an empowering choice or option by some is seen as oppressive by others.

AB: Yes. Let’s take birth control. There’s this idea that, with its development, suddenly women could control their bodies. It led to the sexual revolution. It led to women having more power in the workplace. We think of it in these empowering ways. But it was developed through the exploitation of poor, primarily Black and brown women, using coercive methods in Puerto Rico. White women find power in these technologies and healthcare advances, but they were developed through exploitation and harm in communities of color. And while this is historical, it continues to impact the way that people feel about all sorts of healthcare decisions.

When a doctor recommends an IUD to a Black teenager, that means something different than when a white teenager is recommended an IUD. These historical underpinnings influence how they’re going to receive that care, and also how the doctor is giving that care.

The IUD is a key example of this. There’s been a huge urgency within public health in the US to increase the number of people who have IUDs, and there’s all sorts of government-sponsored programs to get IUDs into as many people as possible, but this tends to be racialized. They tend to target Black and brown women, teenagers, and people in poor communities. These programs will pay for the insertion of an IUD, but oftentimes the removal isn’t part of the equation. We see reproductive stratification when you’re given this power to limit your fertility but not to increase it.

SF: And age, too. I was denied an IUD by four different providers and my insurance company when I was in my 20s. They told me it might affect my future fertility, and I was “too young” to make the decision to have the device implanted.

AB: Even this idea of being “too young” is not equally applied. Some of the people I interviewed for the book who were in their early 20s who were Black were recommended a hysterectomy. But then white women in their mid-30s were told they should keep waiting, that they’re “too young.” Maybe their future husband will want a baby. Maybe they’ll change their mind. Age becomes socially constructed, based on who the person asking for health care is.

SF: You also deal with the notion of women as “hysterical,” and how though the word “hysterics” has diminished in public discourse, all of these conditions of the uterus are said to “cause” women’s fragility, inferiority, unfitness for making decisions about their own health, or even for receiving governmental support.

AB: Even if the language has changed, we haven’t let go of the framework of hysteria. We see it reemerge every time a woman runs for office; all of a sudden her fitness comes into question, and it tends to be around her body and her hormones. We are told that women aren’t capable of making rational decisions for a country because of their body. And then we see it in healthcare. With abortion, specifically, there was this legislative push to force women to view their ultrasound, or to listen to the “heartbeat”—which is actually cardiac activity—in early pregnancy. The idea here was that women don’t know what they’re doing when they get an abortion, that women can’t be trusted to know exactly what an abortion is. If they are shown what they’re doing, they won’t choose that. But there was a lot of research into this, and it didn’t turn out to be true. Women who were forced to view their ultrasound were well aware of what was in their bodies and still actively and confidently chose an abortion.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In my research comparing the experiences of cis women to trans men, I found that the more masculine a doctor perceives you to be, the more agency you have in a medical space. If a medical provider views [the patient] as a more masculine person, doctors tend to give them more agency and will take their pain more seriously.

SF: In the realm of surgical gender-affirming care specifically, there is this tension around altering one’s body. As it pertains to trans folks, people are working themselves into a panic about gender-affirming care. But for cis women who have a uterus, there isn’t much talk about hysterectomy as a process of disfigurement. What do you attribute that to?

AB: A lot of this comes from mayhem laws. There was widespread fear that men would medically disfigure themselves to avoid being drafted. And so a lot of these rules came into play where doctors would be heavily punished if they harmed or destroyed otherwise healthy tissue. This translated to doctors not wanting to provide gender-affirming care because they didn’t want to be viewed as destroying healthy tissue. The way this power was wielded was based on ideologies. We don’t call it mayhem anymore, but that kernel is still there.

SF: My favorite concept in the book is one you coined: the “rowdy patient.” In a way, it seems like a reclamation of the language of mayhem. How might we make use of that language of rowdiness in the world at this moment?

AB: Something I found really beautiful through my interviewees’ stories is how resilient a lot of these communities are, and how, because they can’t rely on their doctors, they rely on each other. There are all sorts of groups forming to help get each other medical knowledge and medical tools. Even if your doctor doesn’t know what’s going on with your body, you can go to your communities, your networks, even on Google Scholar, and bring that research into a clinical space. There are ways to get around these horrible laws, much like with abortion. You don’t really need a doctor to have a medication abortion. You can, oftentimes, have a safe abortion at home if you get the medicines yourself. You know, that was started through grassroots activism: Women in Brazil realized that misoprostol would induce a miscarriage, and they started distributing these pills among their networks and forming groups to accompany each other through their abortions.

There are so many ways that, even as this healthcare system is marginalizing or leaving people behind, communities can come together to take care of themselves and each other. The history of Our Bodies, Ourselves is really a testament to this. The power of women just going on tour and showing each other, this is what your cervix looks like, this is how your vulva works. Just giving each other the knowledge and tools to be able to make healthcare decisions is really, really powerful.

Sara Franklin

Sara B. Franklin is a writer and professor at NYU Gallatin. She lives with her children in Kingston, New York.