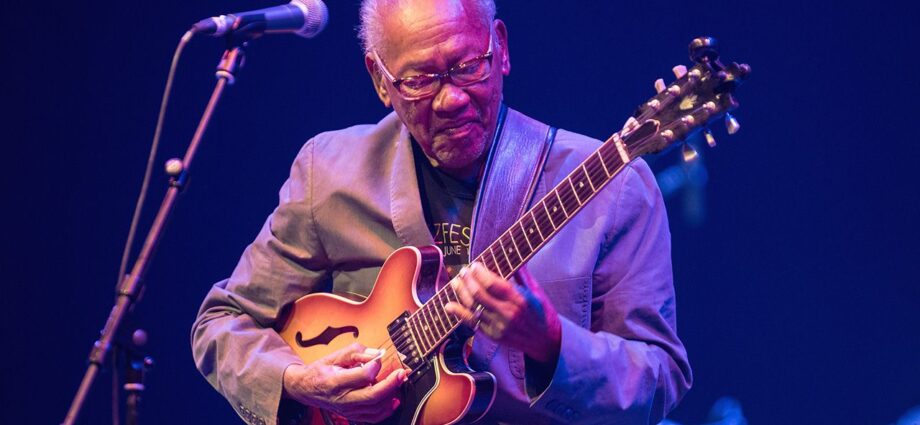

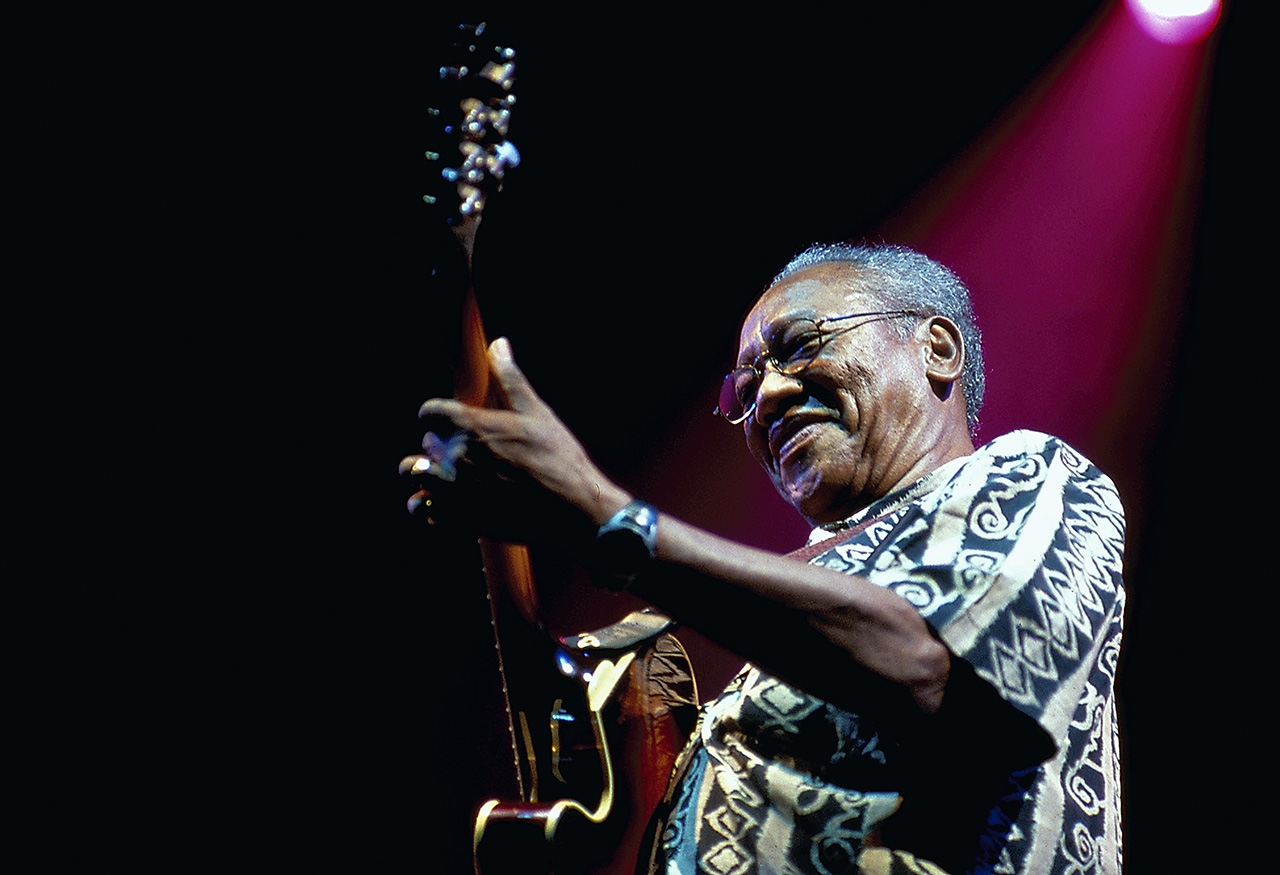

Ernest Ranglin’s innovative guitar style help shape the evolution of ska, reggae and Jamaican jazz. His seven-decade career includes playing on Bob Marley’s earliest songs, arranging the first global Jamaican hit – Millie Small’s My Boy Lollipop – and being part of the house band in Kingston’s renowned Studio One during its prolific mid ’60s period.

His pioneering influence can be heard in the music of The Specials, The Clash, No Doubt, Sublime and many others. Ranglin recently sat down with Guitar World to look back over his life in music.

You played an important role in the evolution of ska and reggae, which paved the way for rocksteady and reggae. How did your experimentation with the shuffle rhythm begin?

“In the early days I was working constantly. I had a job at the Jamaican Broadcasting Station; I’d work during the day for JBS and then late into the night with [producer] Coxsone Dodd.

“We could really read each other’s minds, musically speaking. The first ska session was with Theophilus Beckford – Easy Snappin’. That was it: the ska rhythm. It was clear we had something, even if we didn’t know what we were starting. We did a B-side too, Silky. I actually forgot about it until someone in Japan asked me to sign a copy years later!

“So yes, I was there at the beginning. We were influenced by artists like Louis Jordan, Bill Doggett and Louis Prima, those New Orleans musicians playing that shuffling rhythm. Coxsone and I would talk about what we could do with that beat. It came naturally. I had so many sounds in those shuffling rhythms of New Orleans.

“But we were feeling our own thing too, on the offbeat, the upstroke. Coxsone and I talked about it on a Sunday; on Monday, I went into the studio, arranged the song, and recorded the first ska with Cluett Johnson on bass. Those early recordings started everything that came after.”

What are some of your most memorable sessions from your time at Studio One?

“It was a whole era in just a little amount of time. Coxsone and the musicians needed arrangement and form, and I could do that, bringing in the new rhythm. I put in a lot of time with The Skatalites – I told Don Drummond to use his talents. I remember Eddie Thornton and Blue Buchanon. The early sessions stay with me; they feel like yesterday.”

How did My Boy Lollipop come about?

“It was in England in 1964. Chris Blackwell wanted to bring the Jamaican sound to an international audience. He arranged for me to play some gigs at Ronnie Scott’s. It wasn’t easy at first; but the crowd seemed to relly enjoy my playing, so I was able to go there on a steady basis for nine months!

“Then Chris brought Millie Small to England and asked me to arrange some music for her. I realized My Boy Lollipop was the song we should do. We brought in session musicians who could read music, but they had to learn how to feel that Jamaican shuffle.

“There was only one other Jamaican, Pete Peterson. The rest were English studio musicians. I arranged the tune, and once they got it, it was a turning point for Jamaican music.”

What do you recall about working with Bob Marley?

“He was young when we started working together, but you could already tell that he had something. There was a drive; a presence. I helped guide him early on; I helped with his early tunes – It Hurts to be Alone and Simmer Down and a few others. He later wanted me to help him not only learn guitar but learn to arrange. I think he caught on!”

What about Jimmy Cliff?

“I was Jimmy’s musical director for many years. I helped him develop his true sound and guided and collaborated with him on songwriting. A lot of young musicians came through at that time, brimming with raw talent. I feel like I helped give it shape and structure.”

Prince Buster was another.

“Prince Buster was special. He actually started as an assistant to Coxsone. He played a vital role in developing the Jamaican sound and helping identify and source music. He always stood out, partly because of his background. He had his own ideas and direction.”

We often just used what was available – that limitation often helped create a unique sound

You worked with Lee “Scratch” Perry.

“He was a kind of a genius – completely original. His production methods were like no one else’s. And us working together; you know we brought that sound out together – reggae.”

Toots and the Maytals were another reggae group.

“Toots was always a talented guy. We got along well. I was lucky to collaborate with so many great musicians. Reggae Got Soul – that’s a great tune. We worked closely around that time.”

What was your primary gear on those Studio One sessions?

“It’s hard to remember, exactly, but the setup was very basic. My guitar was a Guild semi-hollow that I bought at Jamaican Broadcasting around 1958; it was a used guitar then, maybe a late ’40s guitar.

“We had old amps from JBS, sometimes Phillips, then later Fender. I think I also used Hadley Jones amps from England. We often just used what was available, and that limitation often helped create a unique sound.”

What’s your current setup?

“I’m not playing too much these days – I’m 93! – but I always liked the clean sound of the Roland JC-120 amp. I played a Gibson for many years, and now I have a hollow-body guitar from Heritage. No effects, just a clean tone. That’s what I like.”

Ska and reggae influenced bands like Madness, The Clash and The Police. How do you feel about influencing a new generation?

“I feel honored – truly. My music and style have had a good life, and I’m grateful they’ve touched people. But it’s not about credit. I know this music heals and helps people. That’s all I ever wanted.”

You recently started a Kickstarter campaign to fund a box set that will document your musical legacy.

“I’m amazed for this opportunity. I wasn’t aware of what things like Kickstarter can do! The plan is to use a little of everything from my career, that I’m finally getting back certain rights too. It’s been a long time coming. I’ve given my life to this music and I feel like I’m beginning to get what’s right and proper.

“We have a new team to build something very special. It’ll be a box set of many different ideas – out-of-print recordings, remastered tracks and new versions. Maybe new songs, too!”

- Ranglin is aiming to raise $50,000 on Kickstarter. The campaign is active now.