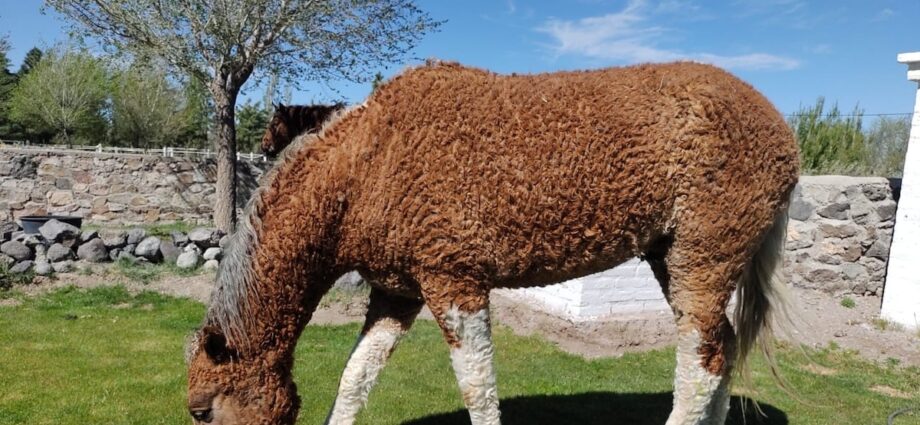

There, in a desolate corner of the Somuncurá Plateau in the Argentine province of Río Negro—where the word “inhospitable” seems to have been invented—Gerardo Rodríguez, a veterinarian, spotted a horse calmly grazing amid the rugged landscape. Seeing any horse in such an isolated, arid region was already unusual, but this one was unlike anything he had ever encountered: Its coat was curly.

Initially, Rodríguez thought the horse’s curly coat indicated it was sick or sweaty, but a gaucho, or horseman, told him something surprising: These curly-haired horses used to be more common before droughts, volcanic eruptions, and other adversities had decimated their population.

The local man offered to sell Rodríguez the horse. Enchanted by the creature, he immediately said yes. His wife, Andrea Sede, felt the same instant connection to the animal. “I’ll never forget meeting him,” she recalls. “He approached us as if he had always been ours.”

This moment sparked the couple’s dream of forming their own herd. Nearly 20 years later, Rodríguez and Sede now have 40 of these curly-coated horses—the only ones of their kind in all of South America—preserving a fascinating and unexpected chapter of Patagonia’s natural history, one that even escaped famed naturalist Charles Darwin, who meticulously documented the region’s flora and fauna during his South American voyage on the Beagle. The evolutionist had heard rumors of these horses but never managed to find them.

(Darwin’s first—and only—trip around the world began a scientific revolution.)

A close up of an Argentine Criollo horse’s curly brown coat and white mane.

Photograph By Andrea Sede

How these wild horses first arrived in Patagonia

To understand the story of Argentina’s curly-haired horses, we must go back several centuries to the Spanish introduction of the first horses to the Americas. In 1535, conquistador Don Pedro de Mendoza was tasked with establishing a colony in the Río de la Plata region, part of what is now Argentina. He crossed the Atlantic with settlers, soldiers, and about 100 horses, including workhorses and fine warhorses from the stables of Cádiz, a city in Spain.

Just six years later, in 1541, the Buenos Aires colony in that region was destroyed and burned by Indigenous tribes resisting colonial abuse. The Spaniards fled, abandoning their possessions—and between 12 and 45 horses. These horses survived and roamed freely across the vast Argentine pampas.

“The escaped horses adapted and reproduced portentously,” explains Dr. Mitch Wilkinson, vice-chair of the International Curly Horse Organization (ICHO) Research Department. “The descendants formed herds of hundreds of thousands of wild horses known as ‘baguales.’”

When the Spanish returned 40 years later, they found not only a booming population—estimated by Wilkinson at 36,000 steeds due to favorable conditions such as abundant food and open plains—but also an unexpected trait: Some horses had developed curly coats, a characteristic not seen in Spain.

What occurred was that new horses imported from Spain were crossed with the feral herds, giving rise to “Criollo” horses—of Spanish descent but born in the Americas. These horses thrived both in the wild and in domestic settings, spreading across Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil.

In 1739, Spanish explorers Cabrera and Solanet documented curly-coated horses among wild herds in Argentina and Brazil. Decades later, Spanish naturalist Félix de Azara also described these horses in his book Quadrupeds of Paraguay, published in Paris in 1801. Even Charles Darwin took note of the horses in his 1868 work The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, citing them as an example of natural selection. Darwin speculated that a random mutation allowed these horses to adapt to their new South American environment. Yet, when he traveled to South America, Darwin never observed curly-coated horses in the wild, leading him to wonder if they had vanished.

You May Also Like

Others, however, attribute their presence to a far more legendary source. According to a local myth, the Knights Templar—a French Catholic military order said to have brought the Holy Grail to the remote Somuncurá Plateau—rode these curly-coated horses, introducing them to the region long before the conquistadors arrived. Though no historical evidence supports this theory, the tale persists, adding an air of mysticism to the breed’s already enigmatic past.

For years, Rodríguez and Sede wrote to international associations in hopes of identifying the lineage of their own horses, but always received the same response: There were no curly-coated horses in South America. Everything changed when they contacted ICHO, and Wilkinson decided to visit them.

His first impression of the horses? “I thought they were unique and beautiful,” he says. DNA samples taken to Texas A&M University’s Equine Genetics Laboratory confirmed the distinctiveness of the Rodríguez-Sede horses, setting them apart from any known breed. Unlike other curly-coated horses, their genetic mutation had not been previously identified. These horses were classified as a type of Argentine Criollo—an ancestral lineage directly descended from the Spanish horses introduced centuries ago.

(Speedy horses evolved only recently, says landmark equine study.)

“Having a curly coat does not in itself make a breed,” Wilkinson explains. “The curly coat is a ‘trait’ caused by a mutation.” While similar traits are found in horses from North America and Siberia, most mutations arise naturally within Indigenous populations isolated by geography. The Patagonian curly-haired horses, untouched by modern European breeds, retain an ancestral genetic connection to northern Iberian ponies like the Gallego and Garrano, although they are slightly larger, standing between 14 and 16 hands (a unit of measurement for horse height).

The adaptive advantages of curly coats remain speculative. Dr. Ernest Gus Cothran, professor of equine genetics at Texas A&M University, notes that while it has been hypothesized since Darwin’s time that the trait might offer a survival advantage in winter, “there is no proof of this.” The harsh Patagonian climate may favor this adaptation, but more data is needed to confirm the theory.

In addition, the Rodríguez-Sede family’s limited funding has prevented them from sending recent DNA samples from their herd—samples essential for advancing genetic studies. Researchers still need to determine the specific genetic mutation responsible for the horses’ curly coats and confirm the inheritance pattern.

Finding hope for preserving these horses

The dream of Rodríguez and Sede’s herd—which later became a desire for preservation—has also not been without challenges. “If we are lucky, we have one or two offspring per year,” says Sede. “Sometimes they die at birth because the mother has no milk, because she did not have enough food to fatten up during the winter, and we do not have money to feed them better.”

Surviving in this harsh environment is no easy feat. Crossing the river from the fertile Alto Valle, with its pear and apple orchards, the stark contrast of this part of Patagonia is striking. There are no trees or mountains—“just stone, stone, and more stone,” explains Sede. In summer, temperatures soar past 86°F under a relentless sun, while winters plunge to -4°F, with several feet of snow blanketing the ground. Water, scarce and precious, is found only in small lagoons formed by melting ice. In any case, Sede’s greatest wish remains simple: “That it rains and the grass grows.”

The problem with preserving these horses is substantially economic, since Cothran believes that once the mutation is found and the genotype of the curly-coated horses of Patagonia is determined, that information can be used to choose the best pair for mating. “If the mutation causes problems when they are homozygous (two identical copies of a gene), the matings can be decided so that homozygotes do not occur,” he explains. If curly coats are desirable for breeders, a test can help increase the frequency of the trait.”

Wilkinson sees a broader problem. “Other breeders in Argentina need to become interested,” he says. “Only a few people know these horses exist.”