It took well over a century for archaeologists to start taking ancient tattoos seriously, with old colonialist attitudes and more contemporary stigmas steering scholars away. What’s more, ancient tattoos can be difficult to study: Tattooing tools are tricky to identify in the archaeological record, and only rarely is ink well enough preserved on mummies to be visible with the naked eye.

But these days, new attitudes and new imaging techniques are fueling a surge of research into ancient and historical tattoos. Today’s scholars have documented evidence of tattooing in cultures around the globe and dated the practice back at least 5,000 years. Aaron Deter-Wolf, an archaeologist with the state of Tennessee and a co-editor of Ancient Ink, the first academic text dedicated to the archaeological study of tattooing, notes that researchers have found more evidence of tattoos on mummies in the past five years than was documented over the previous 150. We asked a few experts in the field about the most memorable ink they’ve encountered—and what they learned from it.

(How scientists are cracking the secrets of the world’s oldest tattoos.)

The lady with divine eyes

This mummy from the Egyptian site Deir el-Medina, once home to the workers and artisans who built the tombs of the pharoahs, has some 30 different tattoos on her arms, shoulders, back, and neck.

Anne Austin

University of Missouri–St. Louis Egyptologist Anne Austin discovered this mummified female in 2014. Before this, evidence for Egyptian tattooing was scant, and scholars theorized that the few known mummies with tattoos—predominantly found on women in ancient Egypt—had been prostitutes.

In reality, Austin says, this woman’s extensive tattoos suggest she was a priestess. Cows, associated with the goddess Hathor, appear on her left arm; baboons, associated with the god Thoth, are on her throat. Most strikingly, one combination tattoo—two sacred eyes flanking a hieroglyph that means “goodness”—is inked over her voice box, on both shoulders, and on her back. All of them, Austin says, would have been visible on someone wearing the Egyptian garments of the time. “So any way you look at her,” she says, “there are divine eyes looking back at you.”

Full sleeves in Siberia

- Pazyryk culture

- Circa 300 B.C.

- Southern Siberia

High-resolution, near-infrared photography allowed researchers to discover unknown tattoos on Saint Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum.

The State Hermitage Museum, Department for Scientific Examination of Works of Art

The elaborate tattoo on the right forearm of this Iron Age nomad shows two tigers and a leopard devouring stags. It was hand-poked with needles, says Deter-Wolf, who recently co-authored a paper on Pazyryk tattooing methods, and he describes it as the work of a master. “It’s not just some caveman with a stick,” he says. “Like weavers or potters, [the artists] learned a skill from someone going back for generations.” Soviet archaeologists discovered the remains of this 50-year-old woman in 1949, but the tattoos on her discolored skin remained hidden until 2004, when she was photographed with infrared-sensitive cameras. The ink looks strikingly modern, Deter-Wolf says. “If you saw someone walking down the street today with this on their arm, you’d be like, ‘Oh, that’s a cool sleeve tattoo.’”

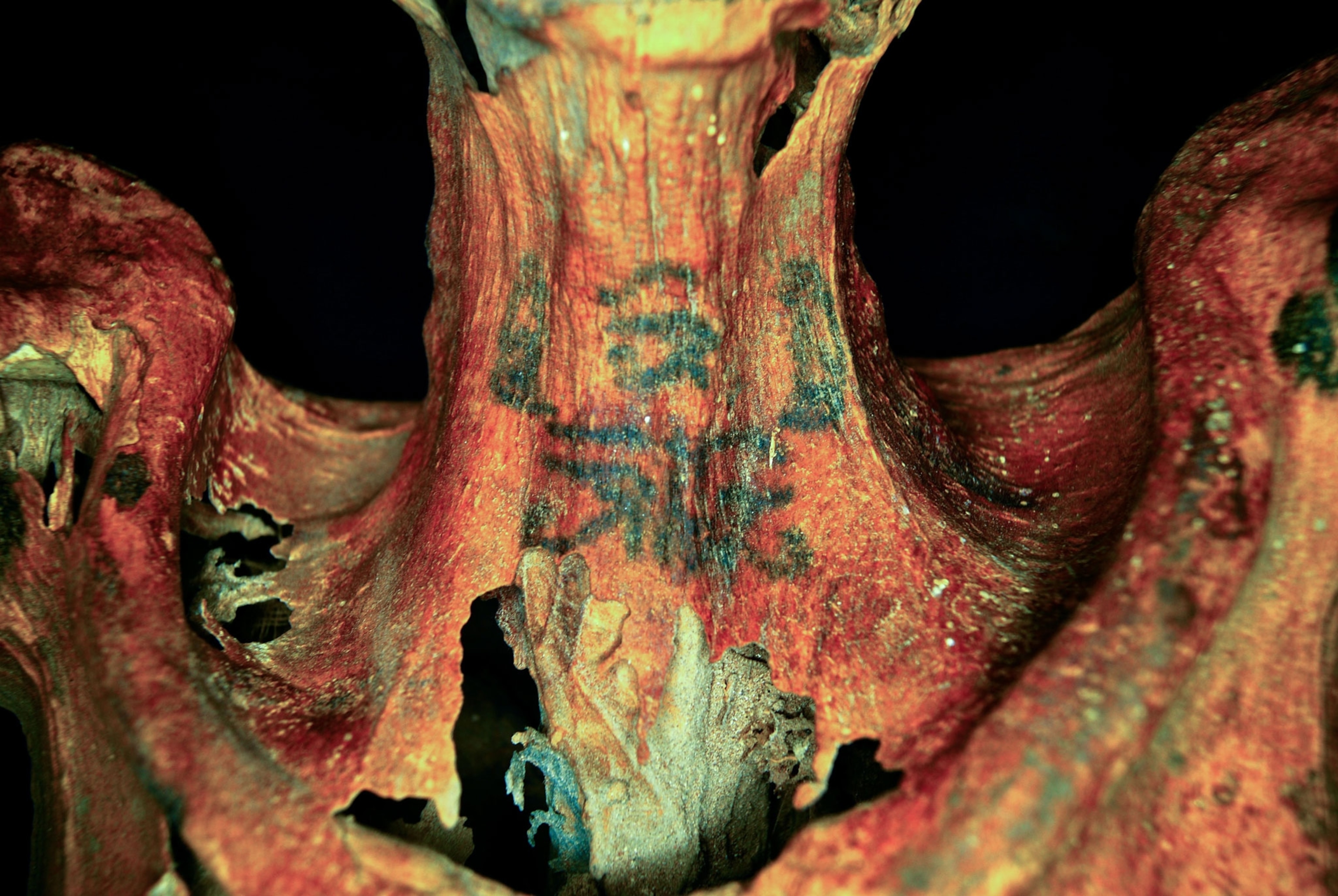

A stormy script

- Ñuiñe culture

- Circa 250 A.D.

- Oaxaca, Mexico

Mummy of Comatlán, Oaxaca, Mexico, Quai Branly Museum, Paris. 2012

Ilán Leboreiro

This naturally mummified body—the only known tattooed mummy from Mesoamerica—was looted from a cave at an unknown date, then brought to Paris in 1889. A French archaeologist originally determined the person was a male, but an analysis led by Mexican archaeologist Ilán Leboreiro in 2012 revealed the mummy to be a female who died in her 30s. Leboreiro suggests she belonged to an elite priestess caste. The glyphs on her shoulder are a form of writing and mention lightning and wind, along with a date: May 5 in the modern calendar. Perhaps, Leboreiro says, the priestess was born on that date or served a weather god whose feast day fell on it. Spanish accounts from the 16th century mentioned the “painted bodies” of Mesoamericans, a line that many scholars once assumed referred to pigments or makeup. This mummy, known as the Momia Tolteca, proved that tattoos existed in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

Fur, fins, and feathers

- Unknown culture

- 1000–1400 A.D.

- Pachacamac, near Lima, Peru

This heavily inked arm was among a trove of mummified body parts discovered at a pre-Columbian citadel outside Lima in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Stylized cats appear on the knuckles and at the apex of the triangle, fish swim along the forearm, and although they’re not pictured here, two birds are also tattooed on the tops of the fingers. Deter-Wolf, who’s studied the mummies of Peru’s central coast, says these creatures collectively reflect Andean cosmology. “With those three animals, you have three levels of the world,” he says. “You have the sky, you have the mountains, you have the water.”

These tattoos were likely applied with pokes from needles, perhaps made from cactus spines, and Deter-Wolf marvels at their precision. “Instead of tattooing the design in black lines, they’re tattooing black fields and leaving the designs open,” he points out. “Really technically interesting and intricate.”

Marks of a warrior

- Kankanaey culture

- 1100–1300 A.D.

- Northern Luzon, Philippines

The mummified remains of the Kankanaey warrior Apo Anno were repatriated to his home community in the Philippines some 80 years after they were looted.

Gunther C.O. Deichmann

Calamities allegedly befell nearby communities after the embalmed body of Apo Anno, a hero of the Indigenous Kankanaey people, was stolen from a cave in the northern Philippines sometime around 1920. Apo Anno, whose mummified remains later turned up at a Manila carnival, was a legendary warrior and demigod, and his tattoos reflect his status, says Lars Krutak, a tattoo anthropologist at New Mexico’s Museum of International Folk Art and a co-editor of Ancient Ink. Among the Kankanaey, Krutak says, “you’d never receive a tattoo unless you had taken another human life in battle.” Apo Anno’s markings include mountain-like shapes, hunting dogs, centipedes, and the scales of snakes. In the 1960s, the body came to the National Museum of the Philippines for study and preservation, then was reburied in a cave in the Philippines in the late 1990s (after which, the surrounding towns were said to have enjoyed bountiful harvests).

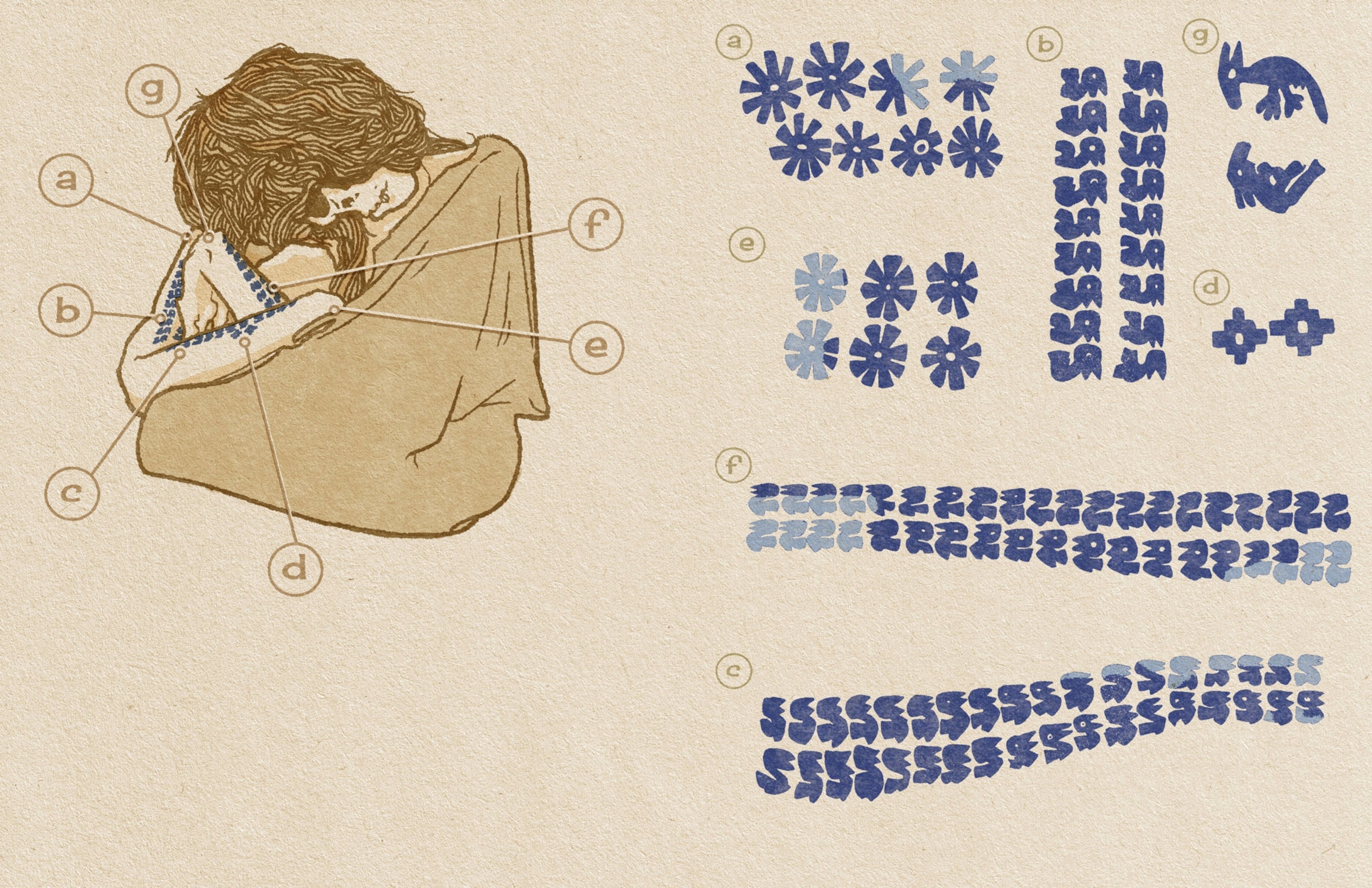

A desert dweller’s designs

- Ica-Chincha culture

- 1250–1550 A.D.

- Near Nazca, Peru

A technical drawing of the mummy from the Naza Desert, now residing in Peru’s Maria Reiche Museum, shows details of the tattoos found on the mummy’s arms and shoulders.

Benoît Robitaille

Spanish conquistadors commonly looted graves in Peru, pocketing gold and jewelry and tossing mummies aside. In the 1980s, a local man found this looted body in the Nazca Desert and trundled it 20 miles on his bike to sell it to archaeologists (who seized it instead). Preserved sitting upright, the body belonged to a male, and Benoît Robitaille, a Canadian archaeologist who studies ancient Peruvian tattooing, says long-haired males in pre-Colombian Peru were likely “engaged with the spirit world.” Asterisks on the shoulder and hand might represent stars.

You May Also Like

The designs, Robitaille says, resemble those found on Peruvian coastal mummies from as far back as 2,000 years before, suggesting remarkable continuity. But there are unique regional touches too: The mirrored animals on the hand, Robitaille says, are likely foxes, the rare mammals that can survive in the parched Peruvian desert.