TOPLINE:

Patients with serum ferritin levels higher than 1000 μg/L show a 91% increased risk for any fracture, with a doubled risk for vertebral and humerus fractures compared with those without iron overload.

METHODOLOGY:

- Iron overload’s association with decreased bone mineral density is established, but its relationship to osteoporotic fracture risk has remained understudied and inconsistent across fracture sites.

- Researchers conducted a population-based cohort study using a UK general practice database to evaluate the fracture risk in 20,264 patients with iron overload and 192,956 matched controls without elevated ferritin (mean age, 57 years; about 40% women).

- Patients with iron overload were identified as those with laboratory-confirmed iron overload (serum ferritin levels > 1000 μg/L; n = 13,510) or a diagnosis of an iron overloading disorder, such as thalassemia major, sickle cell disease, or hemochromatosis (n = 6754).

- The primary outcome of interest was the first occurrence of an osteoporotic fracture after the diagnosis of iron overload or first record of high ferritin.

- A sensitivity analysis was conducted to check the impact of laboratory-confirmed iron overload on the risk for osteoporotic fracture compared with a diagnosis code without elevated ferritin.

TAKEAWAY:

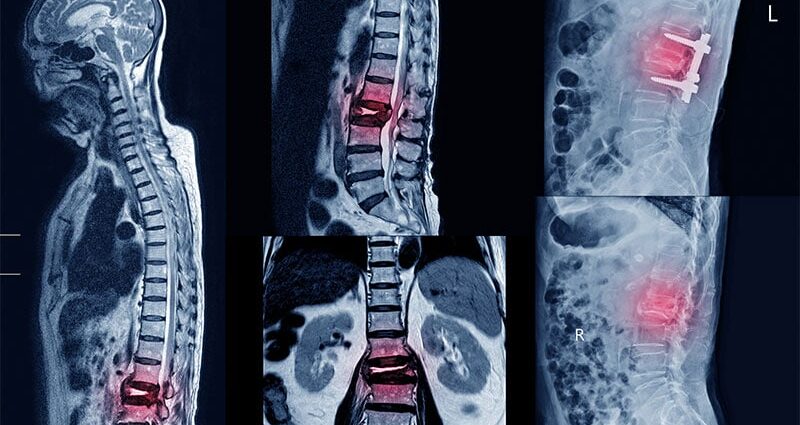

- In the overall cohort, patients with iron overload had a 55% higher risk for any osteoporotic fracture than control individuals (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.55; 95% CI, 1.42-1.68), with the highest risk observed for vertebral fractures (aHR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.63-2.37) and humerus fractures (aHR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.61-2.26).

- Patients with laboratory-confirmed iron overload showed a 91% increased risk for any fracture (aHR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.73-2.10), with a 2.5-fold higher risk observed for vertebral fractures (aHR, 2.51; 95% CI, 2.01-3.12), followed by humerus fractures (aHR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.96-2.95).

- There was no increased risk for fracture at any site in patients with a diagnosis of an iron overloading disorder but no laboratory-confirmed iron overload.

- No sex-specific differences were identified in the association between iron overload and fracture risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The main clinical message from our findings is that clinicians should consider iron overloading as a risk factor for fracture. Importantly, among high-risk patients presenting with serum ferritin values exceeding 1000 μg/L, osteoporosis screening and treatment strategies should be initiated in accordance with the guidelines for patients with hepatic disease,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Andrea Michelle Burden, PhD, Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Chemistry and Applied Biosciences, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland, and was published online in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

LIMITATIONS:

The study could not assess the duration of iron overload on fracture risk, and thus, patients could enter the cohort with a single elevated serum ferritin value that may not have reflected systemic iron overload. The authors also acknowledged potential exposure misclassification among matched control individuals because only 2.9% had a serum ferritin value available at baseline. Also, researchers were unable to adjust for inflammation status due to the limited availability of C-reactive protein measurements and the lack of leukocyte count data in primary care settings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received support through grants from the German Research Foundation. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.