Marijam Did’s Everything to Play For makes a case for rebuilding the culture of gaming, which has become infected with rotten politics.

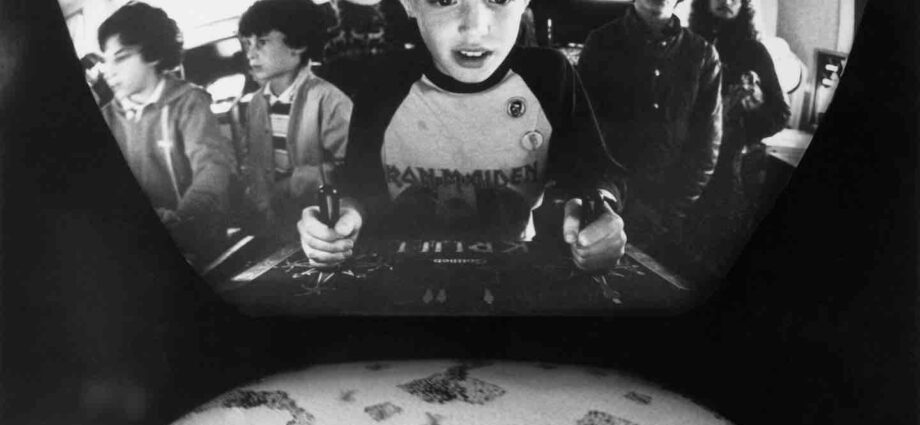

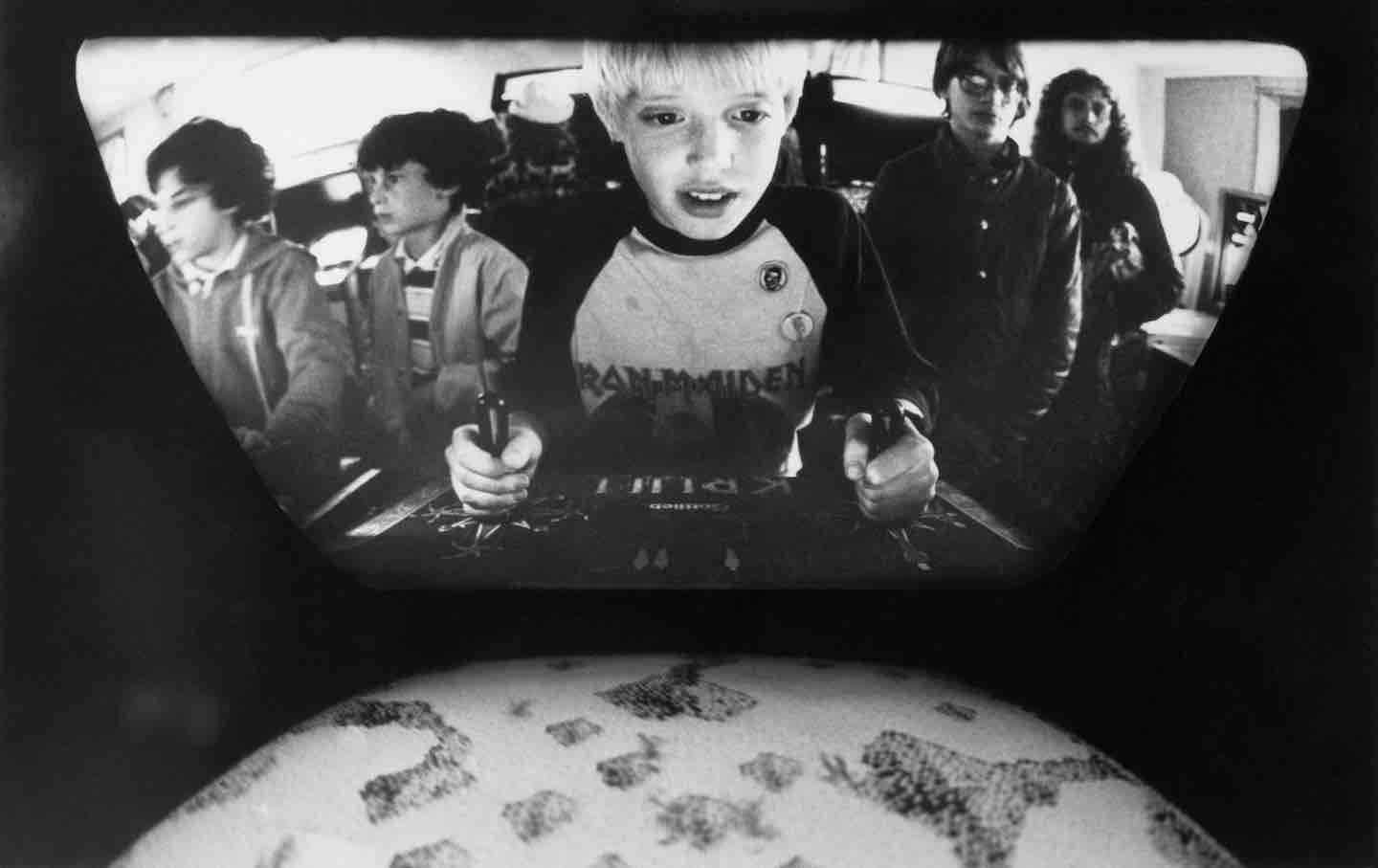

An arcade in Seattle, Washington, 1983.

(Bettmann / Getty Images)

In the 2000s, an ideological battle played out across the fictional cosmos of EVE Online. The MMORPG, which is set 21,000 years in the future, lets its players, alongside their friends and enemies across the Internet, explore a galaxy called New Eden. It is, at times, a tedious game, one premised on mining and trading in order to accrue capital and power, but players can circumvent all that by using real-world money to get ahead of their rivals. With little interference from its makers, the game became a site of fierce political debate and intrigue. Allegiances formed; factions rose and, inevitably, fell—Game of Thrones on a cosmic scale, involving tens of thousands of players at any one time.

Books in review

Everything to Play For: An Insider’s Guide to How Videogames are Changing Our World

by Marijam Did

Buy this book

On one side of EVE Online’s defining conflict was the Band of Brothers, a group of players who acquired powerful in-game enhancements using their own money rather than gathering resources the hard way. On the other side sat a poorer group of players called Goonswarm, who took umbrage with the rapacious techniques of their moneyed counterparts and launched a full-scale war against them. Eventually, the Goonswarm alliance claimed victory, a stunning coup accomplished via virtual espionage: Members infiltrated the private forums of the Band of Brothers, leaking information and launching stinging counterattacks—aided, late in the day, by the defection of the former BoB chairman, Haargoth Agamar. The defeat ultimately cost the Band of Brothers $6,000 in real cash.

In the world of video games, where protest mostly takes the form of negative user reviews and online complaints, stories of more sophisticated player organization and direct action catch the eye. For Marijam Did, author of Everything to Play For: How Videogames Are Changing the World, the showdown between the Band of Brothers and Goonswarm was a catalyzing moment: It broadened her horizons about what video games are capable of and offered a reflection of the world through a lens she was familiar with, namely that of class warfare.

For Did, an activist turned marketer at an acclaimed games studio, Goonswarm’s win also showed that there is much “kinetic energy” to be “directed and charted” in video games during an era when our lives are lived more online, not less. It is Did’s view that the medium has been captured by largely right-wing and neoliberal interests. And she has a point: In a way, Gamergate—the coordinated harassment campaign in 2014 against prominent media critics and gamemakers such as Anita Sarkeesian and Zoë Quinn—never really ended. In recent years, some journalists have dubbed the continued online vitriol directed at women working in video games (those blamed for the medium’s supposed “wokeification”) as Gamergate 2.0. The point is that the loudest voices in the room are warping public discourse around recent and upcoming titles such as Stellar Blade (lauded by latter-day Gamergaters for its unnaturally buxom female protagonist) and Assassin’s Creed Shadows (criticized by the same group for its Black samurai protagonist).

Publishers, meanwhile, including publicly traded companies like Microsoft and Sony, are shedding workers at an alarming rate, cutting costs to maintain bottom lines that keep shareholders and executives happy. For many companies, profits have soared during the past decade as they found novel, compulsively designed ways of monetizing ardent fans in games like Candy Crush Saga and Genshin Impact, actively encouraging them to spend their money on in-game perks. Video games have reached an inflection point, Did opines—now at risk of becoming “eternally entangled in the awkward vines of conservatism and financialisation.”

In Everything to Play For, Did is calling for nothing less than the wholesale reform of an industry she sees as predicated on the exploitation of both its workers and its players, and on the environmentally destructive resource extraction that is fueled by the demands of new hardware. As EVE Online shows, the medium is ripe to be utilized for political ends, yet the left is “late to the party.” The book, then, functions as an impassioned polemic, one aimed at convincing Did’s political comrades that video games do matter: Ignore them at your peril, she warns, lest the industry become a $300 billion mouthpiece for the right.

Did opens Everything to Play For with a “tutorial” to get non-gamers up to speed, essentially a short history of video games. The interesting point she makes is that while game design was “inaccessible to most” in the industry’s early years—a fact she suggests “solidified a stratified cabal” of video game makers and enthusiasts—it was not necessarily inevitable that it should become a medium so heavily associated with men. Video games were partly born in the Pentagon-funded computer labs of the Cold War, where programmers transformed giant military computers into tools of whimsical play. Many women were employed in workplaces such as these as programmers and technicians. Yet now women coders, be it for video games or other computer software, are a definite minority.

Early marketing favored boys, such as a 1973 Atari advertisement that depicted a tall woman in a see-through dress standing next to one of the company’s first arcade machines. The sexist streak in video games continued unabated for the first few decades: From Leisure Suit Larry to Duke Nukem, women were objectified for much of the early history of gaming, and it’s a prejudice that can appear hard-coded into the form. Meanwhile, the militaristic origins of video games became more literal than subliminal in the 1990s and 2000s: 2002’s America’s Army, for instance, was conceived as a “strategic communication device” intended to “inform, educate, and recruit prospective soldiers.” This occurred alongside the proliferation of often xenophobic shooters such as Conflict Desert Storm and Call of Duty. Did’s takeaway, though, is that while it seems as if video games are innately predisposed to appeal to right-leaning young men, not least because of the political and corporate interests that directed the industry’s early years, this is not strictly the case. The thought experiment might be in vain—video games did partly begin at the Pentagon, after all—but Did lets the reader consider the possibility of a form whose early years were not dictated by the “boys’ club” of Nolan Bushnell’s Atari, a company, she notes, whose prototype machines were named after attractive female employees.

Having laid out this history in Everything to Play For, Did follows it up with an effort to correct the prevailing gendered and corporatist narrative around the medium. This aligns with what might be viewed as other correctives to the dominant story of gaming: the DIY modding scene, the rise of independent and art games, and a global network of festivals and junkets that showcase these efforts.

Five years ago at one of these events, a Berlin festival called A Maze, I had a conversation with Robert Yang, a game maker and former assistant professor at NYU Game Center. He described how “video games didn’t really start with an arts culture; they started with a product-based entertainment industry.” It’s only a fairly recent development that there have been “more artistic communities trying to come out of that.” Yang described the process somewhat quixotically: It’s “like we’re reverse-engineering art out of the capitalism that formed video games.”

In her book’s more rapturous passages, Did pushes at the current limits of the ludic imagination, dreaming of gaming equivalents to the Fluxus art movement and the DIY and zine movement fostered by punks in the 1970s. Yet, as she shows with excursions into the medium’s weirder side, these already exist. There is the underground scene clustered around the lo-fi game engine Bitsy; agitprop and leftist games are alive and well; and soon, a video game will be released that is hosted on a solar-powered server. Bearing in mind the “product-based entertainment industry” from which video games sprang, it is arguably a miracle that such subversive works exist at all. But Did’s contention is that these can be more than mere pockets of hope outside the mainstream: There is the potential for them to flourish into the norm.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Did is an idealist who nonetheless reserves stinging critiques for the “boundless, fascinating, grotesque industry” she professes to love—a conflict, I think, many gamers can relate to. She notes that the budgets for the games themselves are so large, with production operating at the scale of gigantic, globalized factories, that “challenging the audience with a progressive agenda is seen by many as a money-losing exercise.” In a key section, Did lambastes hardware manufacturers for their ongoing reliance on conflict minerals such as tin and gold, which are required to create the circuit boards; the harmful impacts of other extractivist industries; and the poor working conditions at factories (mostly in China) where the gaming consoles are assembled. Such is the force with which she makes these arguments that it forces the question: Are video games in fact beyond “rescuing”?

Did doesn’t think so. In 2018, the global profits of the video games industry eclipsed those of the music and film industries combined; by 2028, it will generate half a trillion dollars. Currently, there are over 3 billion active gamers in the world. That’s an enormous captive audience. But for a book that is rooted in structuralist thinking, Everything to Play For lacks a certain context about how games arrived at this point (that is, beyond the industry’s own internal machinations). The rise of video games in the past four decades has broadly coincided with the shrinking of public life and the continued development of technologies like television, personal music-playing devices, and, yes, game consoles, facilitating a rise in private leisure time. Public spaces like libraries and parks have dwindled. In London, where Did used to live, parks have been insidiously privatized. Perhaps the reason why the broader population, including the vast majority of Gen Z, is becoming more online is partly because they have fewer spaces to inhabit in the real world. That trend seems unlikely to be reversed.

Bearing in mind gaming’s growing audience, it’s unsurprising that companies have sought to capitalize on this consumer base. Fans, in particular, find themselves part of a corporate “community” whose very existence is predicated on the idea that their own passion-driven labor can be wielded for commercial gain. There is an argument to be made that video game fandom, which percolated on forums before making the jump to social media and then private Discord servers, is perhaps the progenitor for most forms of modern, online fandom: Taylor Swift’s obsessive Swifties; the so-called “Army” devoted to the K-pop band BTS; the legion of crypto bros who engineer the rise and fall of so-called meme coins while preaching the hyper-capitalist gospel of both Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

For every story Did relays of a populist triumph like that of Goonswarm, or the way the guilds in World of Warcraft divvy up the spoils of a raid in a manner evoking the equitable distribution of a worker-owned co-op, there are instances of fans, either formally or informally organized, pursuing less benevolent ends. When a game launches in a noticeably buggy condition, game developers are labeled as “lazy”; when a writer (usually a woman or a trans person) criticizes a game otherwise broadly celebrated, they are sent death threats. The online discourse around video games is toxic. It would take a monumental effort to counter it. But the medium is not necessarily unique in this regard. One wonders: Is it video games or the Internet itself that needs to be fixed? Applied to hardware, one might ask whether it is the game-console manufacturing process or that of consumer electronics writ large that should be remade.

Did remains unwavering in her optimism and commitment to change. Video games are not just the future of “art, entertainment, and sports,” she suggests, but also of “community organizing.” Online multiplayer games like EVE Online, Fortnite, and Roblox are “closer to social media networks than to linear single-player games.” They are spaces where politics and culture are happening in real time.

At its best, Everything to Play For is invigorating, resonating with the recent unionization gains in the broader video game industry. In its less effective moments, however, the optimism can feel a little misplaced. At one point, Did argues for the potential of authored, stand-alone video games to “invoke social change.” She makes the case for games as art, games that are “subversive, dangerous, risky, generous with varying interpretations and outcomes.” One such example is Pedercini’s Phone Story (2011), a critique of iPhone production that was banned from the App Store just four days after its release. Another is the game Oikospiel Book I (2017): Prior to purchasing it, players can fill out a form revealing their income and the number of members in their household to generate a price they would pay for the game. Did commends such games for their thematic bite, yet she is well aware of how much work remains to be done: “If we want to enjoy our beloved hobby of gaming guilt-free, the entire production line has to be abolished and rebuilt from scratch,” she writes.

In this way, there’s a utopian thrust to Everything to Play For, one delivered with an activist’s zeal. Did’s concluding proclamation, echoing Paul Lafargue, is that “our leisure time is on life support…we ought to have a right to be lazy.” For some people, video games may already be beyond saving—too warped by capitalism, corporations, oppressive design and technology. For everyone else, Everything to Play For has much to offer, including a framework for understanding their prized pastime or chosen profession. It may also provide the jolt some need not to quit on the gaming industry just yet—the motivation to dig in, do the hard work, and reboot it.

Lewis Gordon

Lewis Gordon is a UK-based video game and culture journalist. His work appears in outlets such as Vice, The Verge, and The Onion’s AV Club.