Culture

/

Books & the Arts

/

September 26, 2025

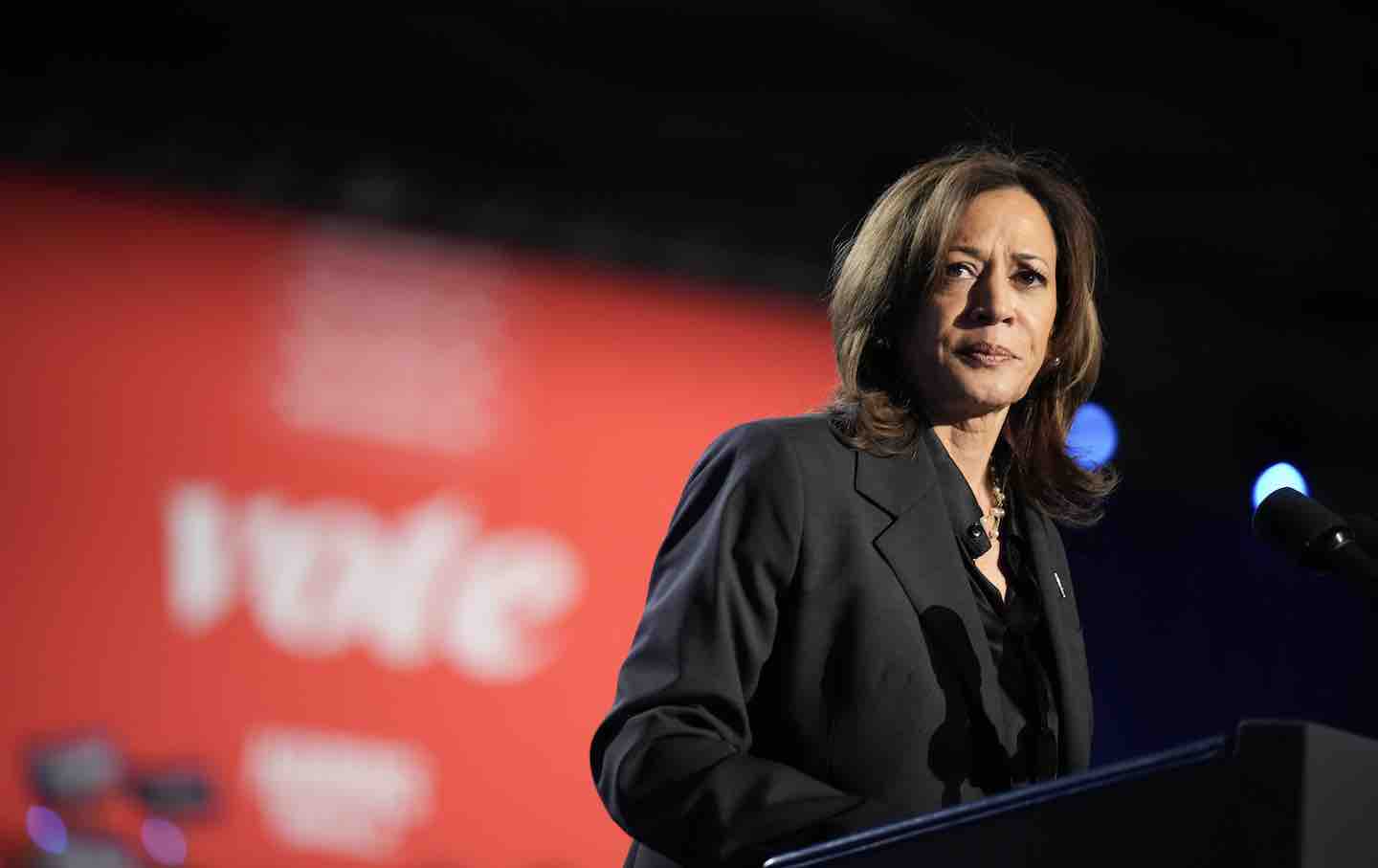

Kamala Harris’s 107 Days offers a devastating indictment of Joe Biden. It also documents the limits of her own politics.

Presidents cast long shadows. Vice presidents are usually doomed to live in those shadows. If presidents are stars on the stage of world history, vice presidents are nervous understudies hidden away behind the scenes. They live in interminable limbo, on call in case some catastrophe (a scandal, death, assassination) requires their elevation. As such transfers of power are not the norm, vice presidents can usually be found in unglamorous busy work, at best breaking tie votes in the Senate and at worst serving as White House gofers. The popular HBO show Veep, which starred Julia-Louis Dreyfus as a hapless vice president, wrung seven seasons of cringy comedy out of the inherent awkwardness and ignominy of the position.

The pathos of being a veep pervades Kamala Harris’s campaign memoir 107 Days. Reflecting on her messy succession, she tells the story of how she ended up taking over the Democratic presidential nomination from Joe Biden last year and eventually losing to Donald Trump. Harris quotes the familiar gibe of John Nance Garner, Franklin Roosevelt’s first running mate, that the job of vice president is not “worth a bucket of warm piss.”

Harris is not the first vice president to air her grievances. In 1962, the master of resentment, former vice president Richard Nixon, wrote Six Crises, a seething effort at reputational rehabilitation that sought to both explain his loss to Kennedy and carve out a political identity independent of Eisenhower. In passive-aggressive form, Nixon complains about Kennedy’s alleged skulduggery in the narrow victory in the 1960 presidential election and makes clear his frustration about Eisenhower’s constantly undermining him. Nixon’s anger was not entirely baseless, either. When asked about what Nixon had contributed to the White House, Eisenhower replied: “If you give me a week, I might think of something.”

107 Days is a very similar book to Six Crises: an exercise in taking stock and blame shifting, with an eye toward a future presidential bid. Harris knows the second presidential victory of Trump is a massive historical disaster and she needs to offer a plausible accounting if she ever wants another chance at the White House, and so 107 Days is her effort to point fingers—just primarily at others.

The major target of these pointed fingers is Joe Biden. It is, 107 Days argues, all his fault: Biden’s selfish decision to run for a second term despite his advanced age created a situation where Harris faced the impossible task of running a truncated campaign of 107 days. Aside from creating a nearly hopeless situation, Biden and his cronies, per Harris, constantly undermined her before and after she was the nominee.

Harris contrasts this destructive behavior against her own loyalty, which arguably also harmed her, since she was unable to separate herself from Biden. But here a lot of blame also falls on Harris’s shoulders. In painting such a devastating picture of Biden, Harris raises questions about her own political judgment. Why did she remain so loyal to Biden even when his own policies and decisions appeared to put the country and hundreds of thousands of people’s lives at risk? In this way, 107 Days is also, mostly unintentionally, an indictment of the kind of clubby elite liberalism that both Biden and Harris benefited from and to which they mostly adhered.

Harris’s recognition of her own complicity creeps in every once in a while. Like Nixon, Harris uneasily mixes gratitude with grudges throughout 107 Days. She writes, “The rapport between Joe and me was genuine. For two people who seemingly couldn’t have been more different, our values were incredibly aligned.” She then adds in the next paragraph that “the president’s approval rating of 41 percent was a ball and chain dragging down my campaign.”

Since Biden was inaugurated as president at the advanced age of 78, realism alone should have dictated that he groom Harris to take charge when and if necessary. Yet, Harris notes, he and the White House did the opposite: They gave her politically risky tasks (such as being the face of the administration’s border policy) and refused to defend her from unfair media attacks.

This was true even after the disastrous debate between Biden and Trump, when a tense Jill Biden did not turn to Harris for solace or advice but instead to demand loyalty. “Are you supporting us?” she asked Harris and her husband, Doug Emhoff. “That’s really important, we need to know.”

Harris could answer honestly yes. She had, at least in her retelling, always been a good soldier and loyal to a fault. Everyone was going to wait for “Joe and Jill’s decision.” As Harris recalls:

We all said that, like a mantra, as if we’d all been hypnotized. Was it grace, or recklessness? In retrospect, I think it was recklessness. The stakes were simply too high. This wasn’t a choice that should have been left to an individual’s ego, an individual’s ambition. It should have been more than a personal decision.

When the dam broke and Biden did withdraw, Harris also still remained loyal. Loyalty meant no public criticism of Biden even where he was clearly wrong, most glaringly in his nearly unwavering support of Israel’s onslaught in Gaza. Harris claims in private that she tried to change Biden’s mind, noting that

I had pleaded with Joe, when he spoke publicly on the issue, to extend the same empathy he showed to the suffering of Ukrainians to the suffering of innocent Gazan civilians. But he couldn’t do it; while he could passionately state, “I am a Zionist,” his remarks about the innocent Palestinians came off as inadequate and forced.

That Harris tried to change Biden’s mind was a good thing, but it’s not hard to miss that when talking about Gaza, she reverts to the gauzy language of empathy without making clear what concrete measures she thought were necessary to end the slaughter. It’s even harder to miss how silent she was in public on the matter. Private pleas for Biden to show some heart were simply an inadequate response to the killing fields of Gaza, which anyone with eyes could recognize as a genocide.

Evasive about her responsibility for Gaza, Harris is critical of herself in retrospect on other matters, though these criticisms are mostly not over policy but messaging. Harris tells readers that she regrets she wasn’t able to sell her brand of centrist liberalism to young people, and she does some self-flagellation over some botched media appearances. One such gaffe occurred when she appeared on The View and was asked, “If anything, would you have done something differently than President Biden during the past four years?” Harris responded, “There is not a thing that comes to mind.” Harris knows this is the wrong answer, but the response she thought she should have given (that she would have appointed a Republican in the cabinet, something she said after the break) is hardly reassuring.

After this appearance, her adviser David Plouffe, a veteran Barack Obama campaign adviser, told her, “People hate Joe Biden.” In her view, this was her gravest error: not acknowledging Biden’s. “Why. Didn’t. I. Separate. Myself. From. Joe. Biden?”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Part of the problem, at least according to Harris, is that Biden’s team seemed to imply that if she were to distance herself from him, his supporters might sabotage her campaign in swing states. But another reason is that her centrist politics were almost identical to his (with Biden indeed being perhaps more willing to criticize the rich than she is). Like Biden, she was a pro-system politician, one who believes the status quo needs reform but not a radical overhaul. The problem for the Democrats is that this pro-system politics allows Donald Trump to absorb all the intense popular anger at the existing order. This is one root of the party’s failure and Trump’s two victories.

In 107 Days, Harris continually touts herself as a prosecutor. Defending her childcare proposal, she says the Republicans “mischaracterized” it as “socialism” but “I call it capitalism and a great ROI [return on investment].” But did Harris truly make a good case for herself and for the Democrats more generally?

Like many liberals, Harris is quick to decry Trumpian “fascism” but refuses to see that this wave of right-wing authoritarianism is driven by the dynamics of capitalist exploitation, social alienation, and economic inequality. She repeatedly praises her “politically astute” brother-in-law Tony West, a trusted adviser and senior vice president at Uber. But she doesn’t acknowledge the reporting that West, to please Wall Street, helped water down her economic message by muting populist critiques of price gouging. This was surely a factor in her defeat, one separate from the selfish arrogance of Joe Biden.

Toward the end of the book, Harris seems to have a glimmer that her politics is not up to the tasks of the moment. Surveying her career, she writes, “I wanted to make changes from inside the system.” Then she reflects that, “in this critical moment, working within the system, by itself, is not proving to be enough.”

This is true and points to a much more radical conclusion than Harris is willing to make. The key is that the Democrats need to break not just with Joe Biden but with neoliberalism as a whole. Status-quo liberal politics has failed, and with 107 Days Kamala Harris has, surely not by design, written one of its obituaries.

Don’t let JD Vance silence our independent journalism

On September 15, Vice President JD Vance attacked The Nation while hosting The Charlie Kirk Show.

In a clip seen millions of times, Vance singled out The Nation in a dog whistle to his far-right followers. Predictably, a torrent of abuse followed.

Throughout our 160 years of publishing fierce, independent journalism, we’ve operated with the belief that dissent is the highest form of patriotism. We’ve been criticized by both Democratic and Republican officeholders—and we’re pleased that the White House is reading The Nation. As long as Vance is free to criticize us and we are free to criticize him, the American experiment will continue as it should.

To correct the record on Vance’s false claims about the source of our funding: The Nation is proudly reader-supported by progressives like you who support independent journalism and won’t be intimidated by those in power.

Vance and Trump administration officials also laid out their plans for widespread repression against progressive groups. Instead of calling for national healing, the administration is using Kirk’s death as pretext for a concerted attack on Trump’s enemies on the left.

Now we know The Nation is front and center on their minds.

Your support today will make our critical work possible in the months and years ahead. If you believe in the First Amendment right to maintain a free and independent press, please donate today.

With gratitude,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

Jeet Heer

Jeet Heer is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation and host of the weekly Nation podcast, The Time of Monsters. He also pens the monthly column “Morbid Symptoms.” The author of In Love with Art: Francoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (2013) and Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays and Profiles (2014), Heer has written for numerous publications, including The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, The American Prospect, The Guardian, The New Republic, and The Boston Globe.