Wikipedia of the Unknown

The profound delight of browsing Wikenigma.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

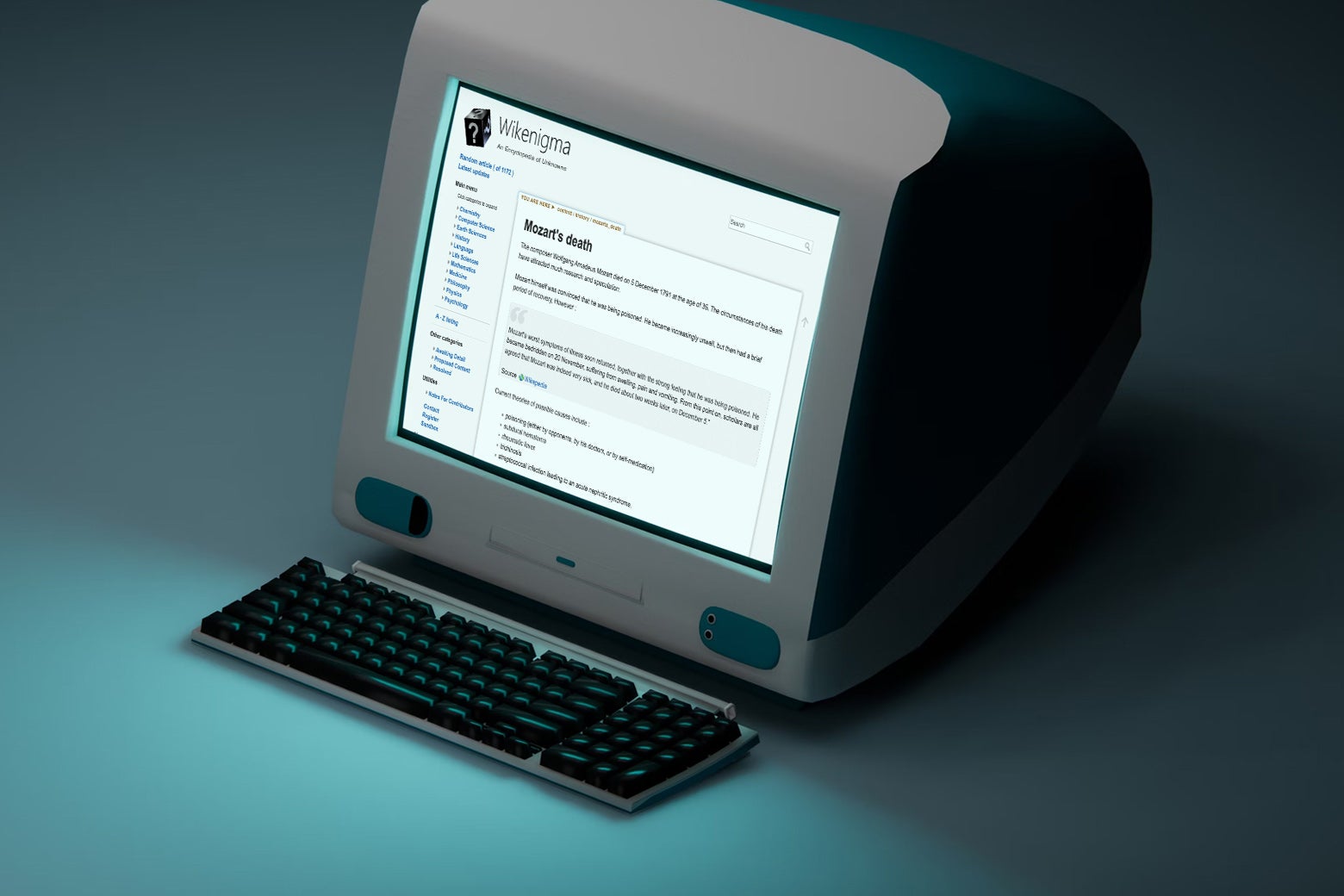

What is the etymology of curmudgeon? What caused Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s death at age 35? Why do many fungi species generate electrical activity? The website Wikenigma, an “encyclopedia of unknowns,” won’t provide answers to these conundrums, and that’s the whole point. In an age of unprecedented access to information, Wikenigma relishes in highlighting the unexplainable across the sciences, history, language, philosophy, and psychology.

The site was created in 2016 by Martin Gardiner, a British art and science investigator and former contributor to the publication Improbable Research, which is behind the Ig Nobel Prize. (The satirical award has honored scientists like those who tried to figure out whether beards really did evolve among humans to protect us from being punched—this won in the Peace category.)

In researching the unusual and seemingly inconsequential in science, Gardiner noticed a lack of resources dedicated to what is not known. So he decided to create his own, working with a small handful of contributors to grow slowly: They reached 500 articles in 2020 and now boast more than 1,100. Gardiner explained to me over email that as a curator, he tries to avoid “ ‘unfalsifiable’ floaty concepts like the famous ‘Does God Have a Beard?’ question.” Instead, he thinks, the best entries are “the ones which most people would (quite reasonably) assume are not unknown. For example, I don’t think many people would guess that no one knows exactly how any of the currently used general anaesthetics work. Or why humans yawn, or why we tend to like flowers or music.”

Although it might seem trivial to group such a wide range of topics—from a crucial medical practice to the lighter fancies of the human mind—into a whole, they encapsulate the complex nature of the human experience. The exact causes of earworms (otherwise known as involuntary musical imagery) are still mysteries, and so are the reasons people suffer from panic disorder or pica. This extends to all areas covered on Wikenigma: The origins of golf (which may have been first played during Roman times, in China, or in the Netherlands) are as disputed as the much more consequential invention of the wheel.

Gardiner explained that with the Ig Nobels, “the ‘hook’ phrase they use is ‘things that make people laugh and then think.’ ” Although with Wikenigma, there’s less humor and Gardiner restrains himself from inserting double entendres and other wordplay, “I did learn from my stint with the Igs that it’s often very very hard to decide whether or not something is ‘trivial’—sometimes the most oddball-sounding things can, in hindsight, turn out to be super important.” For example, Sir Andre Geim was awarded an Ig Nobel in 2000 for levitating a frog via magnetism. In 2010 the University of Manchester physicist was awarded a Nobel Prize for studying graphene’s electromagnetic properties.

And like the Igs, Wikenigma makes scientific research accessible to a broader audience. As you surf around the site, the influence of fellow knowledge source Wikipedia is clear: Wikenigma is open-access and organized clearly by research category. Short articles provide background on the topic, linking to relevant academic work and other entries. Also, like Wikipedia, it enables interaction by allowing for edits and encouraging rabbit holes with hashtags and a feature leading to random articles. (As with Wikipedia, donations to cover server costs are welcomed.)

As Gardiner wrote in his curator rationale, “The idea is to act as a catalyst for curiosity in a general sense—as well as trying to identify possible starting points for (re)cultivating interest in scientific, academic and of course, armchair-based research.”

And there’s much to be discovered about these enigmas: Only three items appear in the “Resolved” category. The most recent is the beeswax wreck, a long-unidentified shipwreck off the Oregon coast that resulted in the local Clatsop tribe having copious amounts of beeswax, which they traded with explorers in the early 19th century. With the material regularly turning up on beaches, the odd occurrence garnered national attention—a piece of the wax was examined at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. But no sign of a boat was found until fisherman Craig Andes (who’s also a bit of a treasure and history enthusiast) began discovering timber in sea caves in the 2010s; historians and researchers studied beams of wood that they now believe most likely came from the Spanish trade ship Santo Cristo de Burgos, which disappeared, laden with beeswax and other trade goods, in the 1690s.

Gardiner explained that this update came from a reader; these exchanges are becoming more frequent as the site continues to grow in popularity: In February of this year, around 100,000 visitors resulted in a total of over 600,000 page views. (It was also shouted out by Annie Rauwerda, who runs the popular social media account @depthsofwikipedia.) Gardiner, who reviews all the content, is the first to admit to the limits of his own knowledge. Specialists often reach out to sharpen the site’s accuracy, he said: “A mycologist pointed out that ‘fungi’ needed their own index section (I had mistakenly put them in the ‘botany’ section). A researcher who’s studying whether or not chewing gum helps concentration alerted me to some updates on the subject—but still no one is quite sure.”

Contributors also provide insight about their specific areas of interest, such as Marco Di Biasi, a 22-year-old Italian computer science student who researched the traveling salesman problem. The enigma involves a list of cities and the distance between each pair; the “salesman” must find the shortest possible route to visit each one just once and return to the original city. As Di Biasi wrote in the Wikenigma entry, “The problem has been examined since the 1930s. but a formal mathematical ‘proof’—which could enable a quick and exact computation, has not yet been found.”

He explained to me that solving such an enigma “may sound obvious, but in computer science, it’s not, because there are infinite possibilities and we have to choose the best one.” He became interested in these sorts of optimization problems after learning about them in school, particularly when the choices made by a computer differ from those of humans: “Even if computer science is a science made by humans, it’s also fascinating how we don’t know everything about it.”

Gardiner hopes for more contributors to join because, “as several agnoiologists [those who study ignorance] have helpfully pointed out, the site will never be finished. And new discoveries and explanations tend to throw up even more new questions.”

Especially in a time of unprecedented levels of online misinformation and attacks on the truth, Wikenigma’s role as a powerful counter seems to be more and more crucial. It’s grounded not only in fact-based information, highlighting the scientific method and researchers dedicated to decoding some of the trickiest areas of study, but also in the humility to admit what can’t be unequivocally understood. Inevitably in this era, such studiously neutral resources are under attack.

Conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation, which is behind Project 2025, intends to “identify and target” anonymous Wikipedia editors it accuses of antisemitism over coverage of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. And right after Donald Trump took power in January, Elon Musk called for a boycott of the site over its description of his infamous inauguration arm gesture. This contested relationship between Musk and the website dates back to at least 2019, when it seemed Musk began to take an interest in his page’s content. Although he bought Twitter perhaps to have total authority over that platform, he can’t control another of the most widely browsed sources of information about him. In a spat on X over the billionaire’s entry, Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales responded to Musk’s call to “defund” the site: “I think Elon is unhappy that Wikipedia is not for sale.”

Wikenigma, like its more mainstream namesake, has made its position on the current internet landscape clear. Gardiner explained that he deleted the site’s X account “when I realized that Wikenigma was, in effect, providing free content for whom Yanis Varoufakis [Greece’s former finance minister] now calls a ‘TechnoBaron.’ That’s quite a polite word for it.”

Gardiner has also taken a firm stance against artificial intelligence scraping, disallowing it in the site’s CC license. Still, “the number of bots which ignore the instructions is growing every day,” he said. Unsurprisingly, the question of whether A.I. will reach or surpass human intelligence levels (known as artificial general intelligence) is the subject of a Wikenigma article. As the article explains, “Note that AGI’s definition is greatly complicated by the lack of agreement about what biological Intelligence itself actually is, and how to define it. Some proponents of AGI suggest the possibility that systems could one day become ‘conscious’ (by some unknown means) though again, there is currently no agreement about what Consciousness itself actually is.” It’s enigmas all the way down.

Get the best of news and politics

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.