Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article as Supplementary Data. Metabolome data and results from data analysis can be found as Supplementary Datasets or at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/studies/S-BSST1724 and https://git.scicore.unibas.ch/zampieri-lab/humanmetabolicmap and interactively browsed at https://zampierigroup.shinyapps.io/HumanMetabolicMap. All data needed to reproduce and rerun statistical tests, analysis and conclusions are supplied as Supplementary Data. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

A detailed description of all data analysis steps is published in this article (Methods and Supplementary Information). MATLAB code is available for download at https://www.zampierilab.org/resources/ and https://git.scicore.unibas.ch/zampieri-lab/humanmetabolicmap.

References

-

Gregori-Puigjané, E. et al. Identifying mechanism-of-action targets for drugs and probes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11178–11183 (2012).

-

Emmerich, C. H. et al. Improving target assessment in biomedical research: the GOT-IT recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 64–81 (2021).

-

Vincent, F. et al. Phenotypic drug discovery: recent successes, lessons learned and new directions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 899–914 (2022).

-

Moffat, J. G., Vincent, F., Lee, J. A., Eder, J. & Prunotto, M. Opportunities and challenges in phenotypic drug discovery: an industry perspective. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 531–543 (2017).

-

Corsello, S. M. et al. Discovering the anticancer potential of non-oncology drugs by systematic viability profiling. Nat. Cancer 1, 235–248 (2020).

-

Pemovska, T. et al. Metabolic drug survey highlights cancer cell dependencies and vulnerabilities. Nat. Commun. 12, 7190 (2021).

-

Subramanian, A. et al. A next generation Connectivity Map: L1000 platform and the first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell 171, 1437–1452 (2017).

-

Way, G. P. et al. Morphology and gene expression profiling provide complementary information for mapping cell state. Cell Syst. 13, 911–923 (2022).

-

Mitchell, D. C. et al. A proteome-wide atlas of drug mechanism of action. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 845–857 (2023).

-

Messner, C. B. et al. Ultra-fast proteomics with Scanning SWATH. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 846–854 (2021).

-

Anglada-Girotto, M. et al. Combining CRISPRi and metabolomics for functional annotation of compound libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 482–491 (2022).

-

Zecha, J. et al. Decrypting drug actions and protein modifications by dose- and time-resolved proteomics. Science 380, 93–101 (2023).

-

Filzen, T. M., Kutchukian, P. S., Hermes, J. D., Li, J. & Tudor, M. Representing high throughput expression profiles via perturbation barcodes reveals compound targets. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005335 (2017).

-

Feng, Y., Mitchison, T. J., Bender, A., Young, D. W. & Tallarico, J. A. Multi-parameter phenotypic profiling: using cellular effects to characterize small-molecule compounds. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 567–578 (2009).

-

Kang, J. et al. Improving drug discovery with high-content phenotypic screens by systematic selection of reporter cell lines. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 70–77 (2016).

-

Badwan, B. A. et al. Machine learning approaches to predict drug efficacy and toxicity in oncology. Cell Rep. Methods 3, 100413 (2023).

-

Zimmermann, M., Zimmermann-Kogadeeva, M., Wegmann, R. & Goodman, A. L. Separating host and microbiome contributions to drug pharmacokinetics and toxicity. Science 363, eaat9931 (2019).

-

Gonçalves, E. et al. Pan-cancer proteomic map of 949 human cell lines. Cancer Cell 40, 835–849 (2022).

-

Frejno, M. et al. Proteome activity landscapes of tumor cell lines determine drug responses. Nat. Commun. 11, 3639 (2020).

-

Cohen, A. A. et al. Dynamic proteomics of individual cancer cells in response to a drug. Science 322, 1511–1516 (2008).

-

van’t Veer, L. J. et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature 415, 530–536 (2002).

-

Behan, F. M. et al. Prioritization of cancer therapeutic targets using CRISPR–Cas9 screens. Nature 568, 511–516 (2019).

-

Douglass, E. F. et al. A community challenge for a pancancer drug mechanism of action inference from perturbational profile data. Cell Rep. Med. 3, 100492 (2022).

-

Nair, N. U. et al. A landscape of response to drug combinations in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 3830 (2023).

-

Bansal, M. et al. A community computational challenge to predict the activity of pairs of compounds. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1213–1222 (2014).

-

Duran-Frigola, M. et al. Extending the small-molecule similarity principle to all levels of biology with the Chemical Checker. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1087–1096 (2020)

-

Ortmayr, K., Dubuis, S. & Zampieri, M. Metabolic profiling of cancer cells reveals genome-wide crosstalk between transcriptional regulators and metabolism. Nat. Commun. 10, 1841 (2019).

-

Dubuis, S., Ortmayr, K. & Zampieri, M. A framework for large-scale metabolome drug profiling links coenzyme A metabolism to the toxicity of anti-cancer drug dichloroacetate. Commun. Biol. 1, 101 (2018).

-

Brunk, E. et al. Recon3D enables a three-dimensional view of gene variation in human metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 272–281 (2018).

-

Wishart, D. S. et al. HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D608–D617 (2018).

-

Campos, A. I. & Zampieri, M. Metabolomics-driven exploration of the chemical drug space to predict combination antimicrobial therapies. Mol. Cell 74, 1291–1303 (2019).

-

Blasi, F., Sommariva, D., Cosentini, R., Cavaiani, B. & Fasoli, A. Bezafibrate inhibits HMG-CoA reductase activity in incubated blood mononuclear cells from normal subjects and patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Pharmacol. Res. 21, 247–254 (1989).

-

Elis, J. & Rašková, H. New indications for 6-azauridine treatment in man. A review. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 4, 77–81 (1972).

-

González-Aragón, D., Ariza, J. & Villalba, J. M. Dicoumarol impairs mitochondrial electron transport and pyrimidine biosynthesis in human myeloid leukemia HL-60 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 73, 427–439 (2007).

-

Cao, S. et al. Tiratricol, a thyroid hormone metabolite, has potent inhibitory activity against human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 102, 1–13 (2023).

-

Lyu, J. et al. Ultra-large library docking for discovering new chemotypes. Nature 566, 224–229 (2019).

-

Diao, Y. et al. Discovery of diverse human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors as immunosuppressive agents by structure-based virtual screening. J. Med. Chem. 55, 8341–8349 (2012).

-

Chilingaryan, G. et al. Combination of consensus and ensemble docking strategies for the discovery of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 11, 11417 (2021).

-

Wierbowski, S. D., Wingert, B. M., Zheng, J. & Camacho, C. J. Cross-docking benchmark for automated pose and ranking prediction of ligand binding. Protein Sci. 29, 298–305 (2020).

-

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

-

Corso, G. et al. Deep confident steps to new pockets: strategies for docking generalization. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.18396 (2024).

-

Mysinger, M. M., Carchia, M., Irwin, J. J. & Shoichet, B. K. Directory of useful decoys, enhanced (DUD-E): better ligands and decoys for better benchmarking. J. Med. Chem. 55, 6582–6594 (2012).

-

Bender, B. J. et al. A practical guide to large-scale docking. Nat. Protoc. 16, 4799–4832 (2021).

-

Hwangbo, H., Patterson, S. C., Dai, A., Plana, D. & Palmer, A. C. Additivity predicts the efficacy of most approved combination therapies for advanced cancer. Nat. Cancer 4, 1693–1704 (2023).

-

Hardy, R. S., Raza, K. & Cooper, M. S. Therapeutic glucocorticoids: mechanisms of actions in rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 16, 133–144 (2020).

-

Caratti, B. et al. The glucocorticoid receptor associates with RAS complexes to inhibit cell proliferation and tumor growth. Sci. Signal. 15, eabm4452 (2022).

-

Snijder, B. et al. Image-based ex-vivo drug screening for patients with aggressive haematological malignancies: interim results from a single-arm, open-label, pilot study. Lancet Haematol. 4, e595–e606 (2017).

-

Gonçalves, E. et al. Drug mechanism-of-action discovery through the integration of pharmacological and CRISPR screens. Mol. Syst. Biol. 16, e9405 (2020).

-

Breinig, M., Klein, F. A., Huber, W. & Boutros, M. A chemical-genetic interaction map of small molecules using high-throughput imaging in cancer cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 11, 846 (2015).

-

di Bernardo, D. et al. Chemogenomic profiling on a genome-wide scale using reverse-engineered gene networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 377–383 (2005).

-

Carraro, C. et al. Decoding mechanism of action and sensitivity to drug candidates from integrated transcriptome and chromatin state. eLife 11, e78012 (2022).

-

Franken, H. et al. Thermal proteome profiling for unbiased identification of direct and indirect drug targets using multiplexed quantitative mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 10, 1567–1593 (2015).

-

Piazza, I. et al. A machine learning-based chemoproteomic approach to identify drug targets and binding sites in complex proteomes. Nat. Commun. 11, 4200 (2020).

-

Ye, C. et al. DRUG-seq for miniaturized high-throughput transcriptome profiling in drug discovery. Nat. Commun. 9, 4307 (2018).

-

Sinha, S., Sinha, N. & Ruppin, E. Deep characterization of cancer drugs mechanism of action by integrating large-scale genetic and drug screens. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.17.512424 (2022).

-

Stokes, J. M. et al. A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell 180, 688–702 (2020).

-

Cappelletti, V. et al. Dynamic 3D proteomes reveal protein functional alterations at high resolution in situ. Cell 184, 545–559 (2021).

-

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

-

Okimoto, R. A. et al. Inactivation of Capicua drives cancer metastasis. Nat. Genet. 49, 87–96 (2017).

-

Ortmayr, K. & Zampieri, M. Sorting-free metabolic profiling uncovers the vulnerability of fatty acid β-oxidation in in vitro quiescence models. Mol. Syst. Biol. 18, e10716 (2022).

-

Zimmermann, M., Sauer, U. & Zamboni, N. Quantification and mass isotopomer profiling of α-keto acids in central carbon metabolism. Anal. Chem. 86, 3232–3237 (2014).

-

Storey, J. D. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 64, 479–498 (2002).

-

Sunseri, J. & Koes, D. R. Virtual screening with Gnina 1.0. Molecules 26, 7369 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Picotti, U. Sauer and K. Weis for helpful feedback and discussions. We thank C. Gruber for advising and helping in optimizing the DHODH inhibitory activity enzyme assay. We thank J. Tuckermann and I. C. Cirstea for sharing the A549 NR3C1 knockout cell line. This work was supported by NCCR AntiResist project funding (180541), SNF Sinergia (CRSII5_189952), Novartis Forschungsstiftung (FN24-0000000612), NIH Research Project (R01) (1R01AI173328-01) and the Desirée and Niels Yde Foundation (543-23) to M.Z. and an ETH research grant (ETH-33 19-2) and the Krebsliga Schweiz (KLS-4124-02-2017) to M.Z. and K.O. P.B. was supported by the Helmut Horten Stiftung and the ETH Zurich Foundation.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Biotechnology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 High-throughput profiling of a large space of chemically diverse perturbations – related to Figs. 1 and 2.

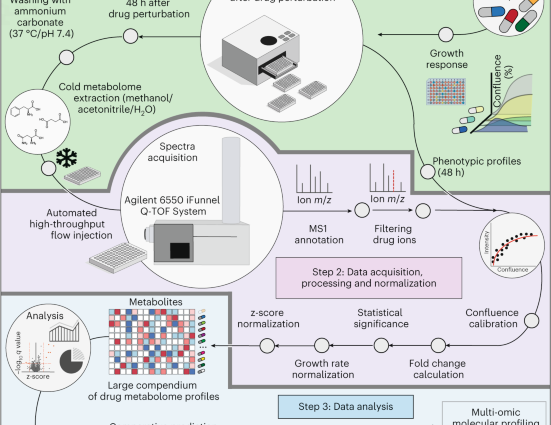

a) Non-parametric estimate of dependency between metabolite fold-changes (FC) and maximum growth rate inhibition. In this example each dot represents log2 FC of alanine and the respective max growth inhibition across all drug perturbations. Shown in red is the locally weighted smoothing regression (LOWESS, that is MATLAB function ‘malowess’) with a window size of 20% of total data for correction of growth rate inhibition. b) Ions are ranked by their pearson correlation with growth-rate inhibition. For the top 10% of ions showing the strongest negative and positive correlation on growth-rate inhibition we performed a pathway enrichment analysis (PEA) and reported metabolic pathways that are significantly altered (hypergeometric test, p < 0.05). c) Log2-transformed distributions of FC differences between biological replicates. Indicated in the box plots are the median and standard deviation of the distribution. Spearman correlation (R2) between each pair of replicates are reported. The low median coefficient of variation (Fig. 2e, that is 10.8%) and the high correlation between replicate fold-change measurements (that is R2 values of 0.89, 0.81 and 0.85 of direct comparisons of FC between the three replicates) reflect the technical and experimental reproducibility of our approach. Data are presented as mean values +/− SD. d) Maximum growth-rate and the area under the growth curve against the herein used metric of growth inhibition compared to DMSO controls. Least square fitting (red line) and the corresponding square of the pearson product-moment correlation coefficients (R2) are reported. e) Volcano plots reporting ion-associated q-value and z-score changes for 4 emblematic drugs: nefazodone, piperacetazine, maprotiline and tandospirone. Indicated are significantly (q-value < 0.05 & |z-score| > 2) changed ions (red). f) Metabolic pathways that are significantly enriched (hypergeometric test, p < 0.05) for metabolites affected by at least one drug (i.e p-value < 0.01). For each pathway we reported the number of drugs inducing metabolic changes that are significantly-enriched for intermediates in the pathway. g) PEA performed on ions that were significantly perturbed by more than 50 drugs (q-value < 0.05 & |z-score| > 2). Only significantly perturbed (hypergeometric test, p < 0.05) metabolic pathways are shown. h) Cumulative variance analysis of drug-metabolite associations. We performed principal component analysis (PCA) of metabolome profiles for the 1’370 drugs with an annotated MoA and counted how many principal components (PC) are needed to explain 90% and 95% of variance. i) For each detected metabolite in our dataset we used the genome scale model of human metabolism (Recon 3D)29 to estimate metabolite connectivity, that is number of metabolic reactions in which the metabolite participate (Material and Methods). j) and l) MS2 profile spectra for DHO and dUMP, respectively. Both MS2 profile spectra were derived from pure standards with 10V collision energy. The non-fragmented parent ion and most abundant fragment ions are highlighted with red diamond and green triangles, respectively. k) MS2 profile spectra for DHO acquired from metabolomics samples from different drug perturbations (MTT, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), pemetrexed (PEX), RTX and LEF). The non-fragmented parent ion and most abundant fragment ions are highlighted with red diamond and green triangles, respectively. m) MS2 profile spectra for dUMP acquired from metabolomics samples from different drug perturbations (MTT, 5FU, PEX, RTX and LEF). The non-fragmented parent ion and most abundant fragment ions are highlighted with red diamond and green triangles, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Predicting drug MoA classes – related to Fig. 3.

a) Schematics of iterative similarity (iSim). b & c) Drug MoAs were defined according to the annotation provided by the Broad Institute7 and the library vendor (Prestwick Chemical Libraries). In total, 316 unique MoA could be annotated, for 150 drugs, no MoA could be derived (Supplementary Table 1). For drug MoA classes with more than 5 drugs, receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed based on iSim drug-drug similarity scores. ROC curves with their respective area under the curve (AUC) are reported for nine representative drug MoAs. d) Comparison of MoA-specific AUC values calculated based on iSim vs spearman correlation or mutual information. On average, iSim outperformed the other two similarity metrics. e) AUC distributions for MoAs of eight anti-infective (blue) or 57 human-targeting (green) drugs. Box plots indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, the sample median and the largest and smallest observations as whiskers. Although, on average similarity among drugs with the same annotated MoA was significantly higher (two-sided t-test p-value = 3.3 × 10−119) than for drug pairs with different MoAs (Fig. 3b), for several MoAs, drug metabolic similarity doesn’t seem to be discriminatory. While it was expected for MoAs related to antimicrobials like 50S ribosomal subunit and cell wall synthesis inhibitors or antiprotozoal agents (Fig. 3a, AUC: 0.51, AUC: 0.52, AUC: 0.50, respectively), for other drug classes directly interfering with metabolism, like cyclooxygenases (AUC = 0.51, Fig. 3a) or folate biosynthesis inhibitors (AUC = 0.53, Fig. 3a) the low recovery was unexpected. We sought potential explanations by focusing on folate biosynthesis inhibitors. Despite the fact that more than 50% of these compounds are bacterial-targeted antifolates (17) and hence have little affinity for the human enzymes, we found that on average, folate biosynthesis inhibitors induced a distinct and significant (p-value < 1 × 10−5) accumulation of Thymidylate Synthase’s (TYMS) substrate deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) as shown in panel f) where, as in Fig. 3h–l, we report metabolic changes that most significantly differentiate folate biosynthesis inhibitors from the rest of the drugs. Highlighted in red are significant (two-sided t-test, p-value < 1 × 10−5) changes. This finding is consistent with the fact that most of the antifolate drugs are annotated as TYMS inhibitors (Supplementary Table 1). Nevertheless, comparative analysis of metabolic changes induced by folate biosynthesis inhibitors unraveled additional changes which lead to two distinct subsets of highly correlating drugs, reflecting diverse mechanisms of metabolic interference within antifolates. For example, several pyrimidine analogues, like 5-fluoracil, trifluridine, gemcitabine and enocitabine tended to cluster separately from sulfonamides, like sulfathiazole, dapsone or sulfamethazine as presented in panel g), where we show a heatmap of pairwise similarity scores between folate biosynthesis inhibitors. h) Ion z-scores averaged across drugs classified as human and non-human targeting folate biosynthesis inhibitors vs p-value from two-sided t-test analysis between metabolic profiles of drugs within the same MoA annotation against all other drugs. Significant changes (p-value < 0.001 & |mean(z-score)| > 0.75) are indicated in red. Similar conclusions as shown for folate biosynthesis inhibitors could be drawn for cyclooxygenases (Extended Data Fig. 2i/j), where the drug-induced metabolic profiles consisted of MoA-specific changes as well as secondary drug specific signatures. Altogether, pairwise drug metabolic similarity suggests that while drugs targeting similar functional processes in the cells – that is same annotated MoAs, are likely to induce similar metabolic changes, distinct drug-induced metabolic changes can reveal previously undescribed drug secondary effects. i) Ion z-scores averaged across drugs classified as cyclooxygenase inhibitors vs p-value from two-sided t-test analysis between metabolic profiles of drugs within the same MoA annotation against all other drugs. Significant changes (p-value < 0.001 & |mean(z-score)| > 0.75, same analysis as for Fig. 3h–l) are indicated in red. j) Heatmap of drug similarity scores of drugs characterized as cyclooxygenase inhibitors.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Comparison of profiling techniques – related to Fig. 4.

a) Cell line comparison of drug growth inhibitory effects. b) Comparison of drug metabolic impact (that is the number of metabolites exhibiting significant changes: q-value < 0.05 & |z-score| > 1) between cell lines. c) Distribution of pearson correlation coefficients comparing the same or different drug-induced metabolic changes in 2 different cell lines (n = 400 and 157708, respectively), d) when only considering drugs with ≥20 (n = 146 and 20808, respectively) or e) ≥ 50 responsive metabolites per drug in both cell lines (n = 67 and 4328, respectively). c-e) Box plots indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, the sample median and the largest and smallest observations as whiskers. P-values are derived from a two-sided t-test. f) Comparison of MoA-specific AUC values calculated from iSim drug-drug similarity in each cell line after 48 hours of drug exposure. g) Comparison of AUC values calculated from iSim drug-drug similarity estimated from drug profiles in the same cell line 24 and 48 hours after drug exposure. h) For each dataset, we reported the total number of profiled drugs and the number of drugs within one of the 64 MoAs containing more than 5 drugs in the Prestwick library. i) Distribution of MoA-specific AUC values for the five profiling techniques (n=66, 50, 60, 49 and 24, respectively). Data are presented as mean values +/− SD. j) Spider plot representation of MoA-specific AUC values. Each dimension represents one of the 64 MoAs. For MoAs with less than 5 drugs AUC values were not estimated. For each MoA the technique yielding the highest AUC was color coded in panel k).

Extended Data Fig. 4 HMG-CoA reductase assays and drug metabolization – related to Fig. 5.

a) HMGCR activity measured by in vitro coupled enzyme assay. A no enzyme control, as well as a DMSO mock control (0.5%) were included. Here we report mean and standard deviation of HMGCR activity inhibition estimated across three biological replicates for 8 drugs at different concentrations and 9 biological replicates for controls (DMSO/no enzyme). b-c) Raw ion intensity averaged over three biological replicates for two selected ions with m/z mapping to 435.273 and 214.945 kDa. Each dot corresponds to the treatment with one Prestwick compound. Highlighted in red are the samples corresponding to simvastatin b) and brivudine c). Data are presented as mean values +/− SD.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Predicting drug effects based on metabolome profiles – related to Figs. 5 & 6.

a) Schematic of leflunomide drug mechanism of action. b) Distribution of drug similarity derived by spearman correlation, mutual information and iterative similarity. The top 1% of drug pairs is indicated with dashed red lines. All drug pairs are indicated by blue circles and the drug pair leflunomide-tiratricol as black, leflunomide-azaribine as red and leflunomide-dicumerol as green circles. c) Z-scores changes and standard deviation over time (1, 5, 24 and 48 hours) and concentration (1, 10 and 50μM) of dihydroorotate upon tiratricol and dicumarol treatment (n = three biological replicates). d) Heatmap of metabolic (iSim) similarity between leflunomide and drugs showing a significant increase in (S)-dihydroorotate. e) Comparison of docking scores reported in Fig. 5k/l derived from the AutoDock vina and DiffDock-L method (see Material and Methods). f) Percentage of GR signal in the nucleus by treatment condition. For each treatment, biological triplicates were obtained, where for each replicate (that is well of a 96-well plate) 67 separate sections were imaged and the nuclear and cytoplasmic location of tagged glucocorticoid receptors was analyzed using ImageJ (see Material and Methods). Shown for each treatment condition is the distribution of all 67 data points of each replicate of GC translocation. g) Two-sided t-test as performed in Figs. 3h–l and 6a between 6 reprofiled GR agonists (10μM and 48 hours) against all non-GR agonists in the Prestwick Library screen in either A549 wt or A549 NR3C1 cells. Indicated are significant (p-value < 0.001 & |mean (z- score)| > 0.75) changes (red). h) Heatmap of metabolic (iSim) similarity between known GR agonists and drugs with different drug MoA that showed high metabolome similarity to one or more of the here shown GR agonists. i) Representative immunofluorescence images showing nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of GR (green) in A549 cancer cells upon treatment of DMSO (0.1%), methotrexate, cortisone, dexamethasone (each at 10μM), bezafibrate, delavirdine, ziprasidone and etifenin (each at 1 and 10μM). DAPI is used as nuclear staining (blue) (n = 3). Included is a schematic of expected translocation of GRs into the into the nucleus if a drug is acting as GR agonist.

Supplementary information

Reporting Summary

Supplementary Table 1

Metainformation_Drugs (All needed metainformation of screened drugs (name, position, Prestwick number, Therapeutic class, Therapeutic effect, Target type, Target name, Target mechanism, drug MoA annotation, Gene name of drug target, Drug SMILES)) / Metainformation_Ions (All needed metainformation of annotated ions (Annotation, Ion m/z, Annotation IDs, Ionization)) / mean log2-FC (Dynamic metabolic changes during drug treatments (mean log2 FC) relative to unperturbed A549 cancer cells) / standard deviation (Standard deviation of mean log2 FC values during drug treatments) / p–values (Statistical significance (Pvalue, t-test) of metabolic changes during drug treatments) / q–values (Adjusted statistical significance (BHFR) of metabolic changes during drug treatments) / z-scores (z-score normalized mean log2 FC).

Supplementary Table 2

Replicate1_Time (Time of growth monitoring of 1,520 drug perturbations run in two replicates (here for replicate 1)) / Replicate1_Confluence (Confluence values (percent of well covered by cells) of growth monitoring of 1,520 drug perturbations run in two replicates (here for replicate 1)) / Replicate2_Time (Time of growth monitoring of 1,520 drug perturbations run in two replicates (here for replicate 2)) / Replicate2_Confluence (Confluence values (percent of well covered by cells) of growth monitoring of 1,520 drug perturbations run in two replicates (here for replicate 2)) / GrowthParameters (Averaged growth parameters (Change of confluence relative to DMSO control, Maximum Growth Rate, time until maximum growth rate is reached, Minimum growth rate, time until minimum growth rate is reached, Area under the growth curve) derived from analysis of provided growth curves).

Supplementary Table 3

LocalityScore(S) (Sum of metabolite z-scores weighted by the respective distance from each enzyme in a genome-scale metabolic model of E. coli metabolism.) / LocalityScorePvalue(SPval) (Metabolic pathways with an overappresentation of enyzmes proximal to the largest drug-induced metabolic changes are individuated using a hypergeometric test analysis. Enrichment analysis Pvalues corrected for multiple tests are reported (qvalues).) / MetaboliteGeneDistanceMetric (Distance of each given metabolite to a gene in the network) / TherapeuticClassesGeneTargest (Gene targets of all drugs in a therapeutic class).

Supplementary Table 4

iSim_A (A value derived from iSim approach of one to another drug) / iSim_CsIte (CsIte value derived from iSim approach of one to another drug) / iSim_Cs (Cs value derived from iSim approach of one to another drug) / iSim_Ps (Ps value derived from iSim approach of one to another drug) / MutualInformation (Similarity value of one to another drug derived from mutual information) / SpearmanCorrelation (Similarity value of one to another drug derived from Spearman correlation) / Chemical similarity (Chemical similarity (based on SMILES codes) derived from Tanimoto distance analysis).

Supplementary Table 5

Investigated_Drug_MoA (Names of all MoA classes with more than five drugs, area under the curve values from ROC curve analysis, number of drugs in the MoA Class, drug names) / t-test_p-values (Pvalues per metabolite and MoA class from t-test comparing drugs of an MoA class to all other drugs) / mean_zscores_metabolites (mean z-score per metabolite across all drug perturbations of an MoA class) / PEA_p-values (Pvalues per metabolic pathway (KEGG) and MoA class from pathway enrichment analysis (PEA) using all drugs from an MoA) / PEA_q-values (qvalues per metabolic pathway (KEGG) and MoA class from PEA using all drugs from an MoA) / mean_ zscores_pathways (mean z-score per metabolite pathway across all drug perturbations of an MoA class) / median_zscores_pathways (median z-score per metabolite pathway across all drug perturbations of an MoA class).

Supplementary Table 6

Metainformation_Drugs (All needed metainformation of rescreened drugs (name, drug MoA; for more information, see Supplementary Table 1)) / Metainformation_Ions (All needed metainformation of annotated ions (Annotation, Ion m/z, Annotation IDs)) / growth response time (Time of growth monitoring of 400 drug perturbations in three cell lines run in two replicates (here for replicate 1, followed by replicate 2)) / growth response confluence (Confluence values (percent of well covered by cells) of growth monitoring of 400 drug perturbations in three cell lines run in two replicates (here for replicate 1, followed by replicate 2)) / z-scores (z-score normalized mean log2 FC (A549, Hs578T, SK-OV-3, timepoint 1 (24 h), followed by timepoint 2 (48 h))) / growth rate parameters (Averaged growth parameters (Change of confluence relative to DMSO control for A549, SK-OV-3 and Hs578T)) / mean log2-FC (Dynamic metabolic changes during drug treatments (mean log2 FC) relative to unperturbed cancer cells (A549, Hs578T, SK-OV-3, timepoint 1 (24 h), followed by timepoint 2 (48 h))) / standard deviation (Standard deviation of mean log2 FC values during drug treatments (A549, Hs578T, SK-OV-3, timepoint 1 (24 h), followed by timepoint 2 (48 h))) / p-values (Statistical significance (Pvalue, t-test) of metabolic changes during drug treatments (A549, Hs578T, SK-OV-3, timepoint 1 (24 h), followed by timepoint 2 (48 h))) / q-values (Adjusted statistical significance (BHFR) of metabolic changes during drug treatments (A549, Hs578T, SK-OV-3, timepoint 1 (24 h), followed by timepoint 2 (48 h))) / iSim_Cell Line Comparison (A value derived from iSim approach of one to another drug profiled within one cell line and one timepoint) / Meta_Transcriptomics (Metainformation of drugs profilied by transcriptomics used in the comparative analysis of multidimensional profiling techniques) / iSim_Transcriptomics (Similarity value (iSim) of drugs profilied by transcriptomics used in the comparative analysis of multidimensional profiling techniques) / Meta_CellPainting (Metainformation of drugs profilied by cell painting used in the comparative analysis of multidimensional profiling techniques) / iSim_CellPainting (Similarity value (iSim) of drugs profilied by cell painting used in the comparative analysis of multidimensional profiling techniques) / Meta_ChemicalGenomics (Metainformation of drugs profilied by chemical genomics used in the comparative analysis of multidimensional profiling techniques) / iSim_ChemicalGenomics (Similarity value (iSim) of drugs profilied by chemical genomics used in the comparative analysis of multidimensional profiling techniques) / Meta_Proteomics (Metainformation of drugs profilied by proteomics used in the comparative analysis of multidimensional profiling techniques) / iSim_Proteomics (Similarity value (iSim) of drugs profilied by proteomics used in the comparative analysis of multidimensional profiling techniques) / Comparative_AUC_Analysis (AUC values derived from ROC curve analysis of drugs within an MoA class across different multidimensional profiling techniques).

Supplementary Table 7

Metainformation_Drugs (All needed metainformation of rescreened drugs (name, drug MoA; for more information, see Supplementary Table 1)) / Metainformation_Ions (All needed metainformation of annotated ions (Annotation, Ion m/z, Annotation IDs)) / mean log2-FC (Dynamic metabolic changes during drug treatments (mean log2 FC) relative to unperturbed cancer cells (A549wt, A549NR3C1 knockout, timepoint 1 (1 h), timepoint 2 (5 h), timepoint 3 (24 h), timepoint 4 (48 h), for enzyme inhibitors: drug concentration 1 µM, 10 µM, 50 µM, for GCR agonists: drug concentration 10 µM)) / z-scores (z-score normalized mean log2 FC (A549wt, A549NR3C1 knockout, timepoint 1 (1 h), timepoint 2 (5 h), timepoint 3 (24 h), timepoint 4 (48 h), for enzyme inhibitors: drug concentration 1 µM, 10 µM, 50 µM, for GCR agonists: drug concentration 10 µM)) / standard deviation (Standard deviation of mean log2 FC values during drug treatments (A549wt, A549NR3C1 knockout, timepoint 1 (1 h), timepoint 2 (5 h), timepoint 3 (24 h), timepoint 4 (48 h), for enzyme inhibitors: drug concentration 1 µM, 10 µM and 50 µM, for GCR agonists: drug concentration 10 µM)) / p-values (Statistical significance (Pvalue, t-test) of metabolic changes during drug treatments (A549wt, A549NR3C1 knockout, timepoint 1 (1 h), timepoint 2 (5 h), timepoint 3 (24 h), timepoint 4 (48 h), for enzyme inhibitors: drug concentration 1 µM, 10 µM and 50 µM, for GCR agonists: drug concentration 10 µM)) / q-values (Adjusted statistical significance (BHFR) of metabolic changes during drug treatments (A549wt, A549NR3C1 knockout, timepoint 1 (1 h), timepoint 2 (5 h), timepoint 3 (24 h), timepoint 4 (48 h), for enzyme inhibitors: drug concentration 1 µM, 10 µM and 50 µM, for GCR agonists: drug concentration 10 µM)) / TTest_GCR_wt_KO_Signature (Pvalues and mean z-score per metabolite across all six retested GCR agonists against all non-GCR drugs profilied in the initial Prestwick library screen, seperately analyzed in A549wt and A549 NR3C1 knockout cells) / Top predictions (List of most similar 0.3% of drug–drug pairs, with drug name, drug MoA, drug therapeutic class and drug–drug similarity scores).

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Schuhknecht, L., Ortmayr, K., Jänes, J. et al. A human metabolic map of pharmacological perturbations reveals drug modes of action.

Nat Biotechnol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02524-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02524-5